Estimating the Truth

The 50-50-90 rule: Anytime you have a 50-50 chance of getting something right, there’s a 90% probability you’ll get it wrong. — Andy Rooney

When you say that someone’s “nice,” you’re essentially claiming that when you interact with that person, there’s a better than average chance that he/I will be nice to you.

Of course, one’s evidence for these claims comes from a variety of sources—personal experiences, recounted tales, amazing blog posts—yet no matter how you reached your conclusion that I’m a nice person, you are, at the core of the statement, making a probability estimate:

More likely than not, if I interact with Jake, he will be nice to me.

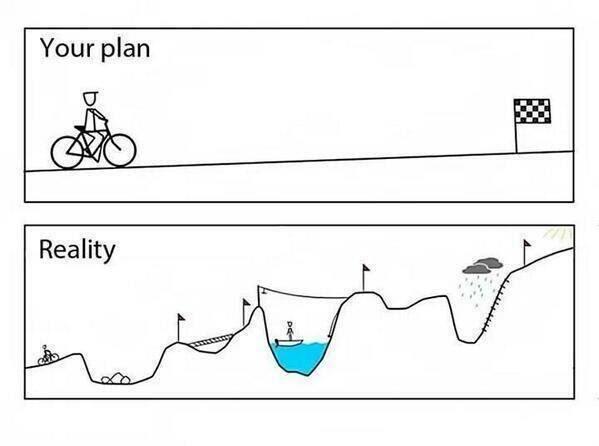

But what we know from social psychology is that humans are not always that great at probability estimates.

Let’s consider an example: Of the following strings of letters (H for heads; T for tails) which is more likely to occur when flipping a coin

H T H H T T T H T H

H H H H H H H H T H

Naturally, we want to say the top line is more likely; however, both share the exact same probability of occurring. But because the top line of numbers looks more “similar” to what we’ve experienced in the real world, we assume it’s more

And this called the “representativeness heuristic.”

Heuristic is just the fancy way of saying “mental shortcut.” Instead of processing ever minor detail of a situation, we simply use a heuristic to come up with a quick answer.

For example, let’s say you’re going shopping for laundry detergent. Research has shown that people, on average, spend a total of eight seconds from the time they walk into the aisle to when they select their detergent.

Eight seconds.

That’s pretty much the entire length of time it takes to walk to the boxes of detergent.

Capitalizing on this speedy selection time, stores will often put their own brand in an orange box right next to the Tide collection. Because people so strongly associate orange with Tide, people use that as their heuristic to make a decision. That is, they don’t even take the time to mentally process the name on the front of the box; they see orange, they grab it.

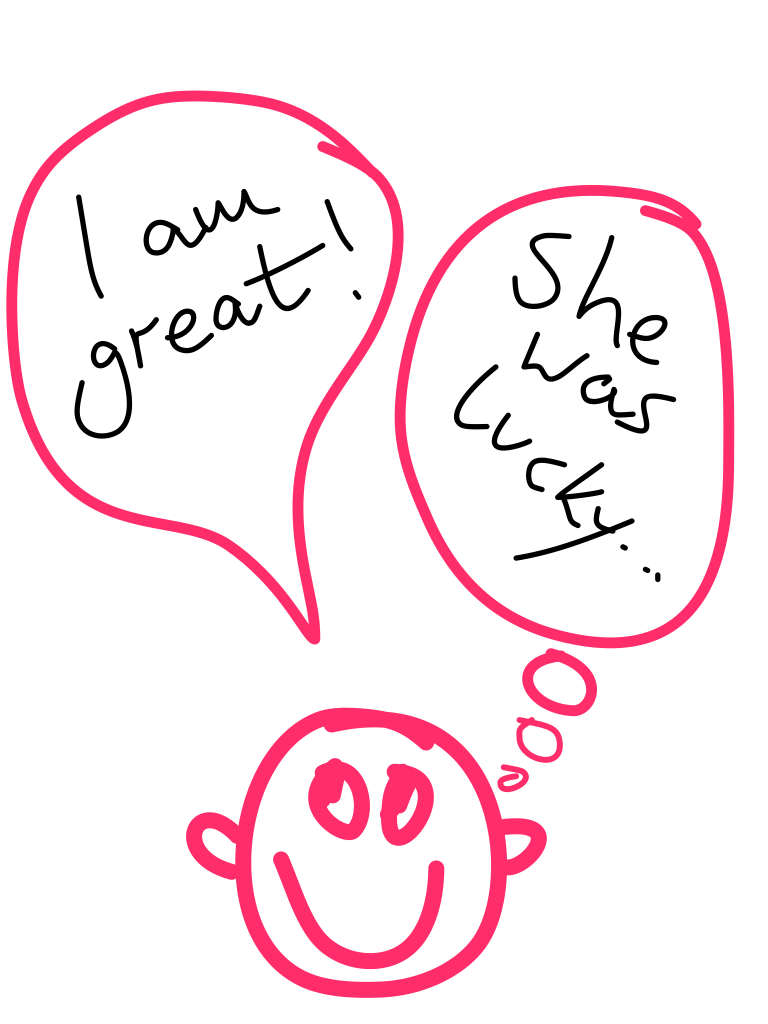

The representativeness heuristic is also one of the basic mental processes underlying stereotypes. For example, if you were to see me with my untamed hair and laissez faire beard, you’d likely think: “That person is homeless.”

Because you have a “concrete exemplar” (i.e. a mental prototype) of what homeless people look like, anyone that resembles it, automatically seems more likely to be homeless. (Wherein the truth of the matter is that I’ve been working past midnight three nights in a row. So pity me—sulking is all I have left.)

Thus, we have to be careful when we make these automatic probability assumptions about people and things (e.g. “that toaster looks like my old one that always burned the toast; this one must be bad, too”). For even though these heuristics can be useful, you’re the one likely burning the toast.

Probably,

jdt

I can’t think of anything witty, but I had to respect you dropping the bomb on us about a ‘laissez faire beard’.

Haha You needn’t be witty to respond, but yes, my beard is getting out of hand. The first thing one of my advisers said to me today was: “Wow. Aren’t you starting to look like a graduate student.”

This wasn’t a compliment.