The Formula for Charisma

Charisma is not just saying hello. It’s dropping what you’re doing to say hello. — Robert Brault

People have told me I’m charismatic. And by people, I mean my mother. And in that moment, she was being sarcastic [the waitress just didn’t understand the complexity of my pun]. Even still, I have clung to that compliment to this day, using it as objective evidence that I am in fact charismatic.

However, this faulty use of logic nonetheless prompts a more serious consideration: Is charisma an “objective” personality trait that you either have don’t? Or is it more so construed in the “eye of the beholder?”

Although this question is somewhat philosophical in nature, research supports the idea that charisma is really determined by how the perceivers themselves feel after interacting with someone.

For example, if a charismatic person isn’t able to make someone feel that they’re charismatic, they won’t be perceived as charismatic (whereas with something like honesty, even if the other person thinks you’re lying when you’re telling the truth, you’re still being honest).

So what exactly does a perceiver need to feel in order to think someone’s charismatic?

At first blush, you can rightly assume that the charismatic make others feel good. That is, whether they make you feel special or happy or important, charismatic people improve your mood. And there is a lot of research supporting this.

However, further research qualifies this finding by showing it’s not just positive emotions that influence perceptions of charisma, but positive emotions plus heightened levels of arousal.

In psychology, physiological arousal refers to the activation of your sympathetic nervous system, or what we typically describe as feeling “energetic” or “alert.” When we then combine this state of arousal with positivity or negativity (i.e., what researchers call “valence”), you get the spectrum of emotions.

For example, feeling excited is both a positive and highly arousing emotion, whereas feeling relaxed is also a positive emotion but one associated with low arousal. On the flip side, you can compare something like anger (which is negative and highly arousing) to something like sadness (which is also negative but elicits low arousal).

In regards to charisma, researchers have found that charismatic individuals don’t simply make their followers feel positive; they make them feel positive and highly aroused. For example, an enthusiastic speaker will be perceived as more charismatic than a content or relaxed speaker.

In fact, one team of researchers examined this by studying two professors who were both positively rated by their students. At different points throughout the semester, the students were asked to rate their mood in class as it applied to arousal (e.g., “To what extent do you feel active in class today?”).

And with over 120 students across five weeks of testing, the researchers found that the professor who elicited greater arousal (even though both were rated positively) was perceived to be more charismatic.

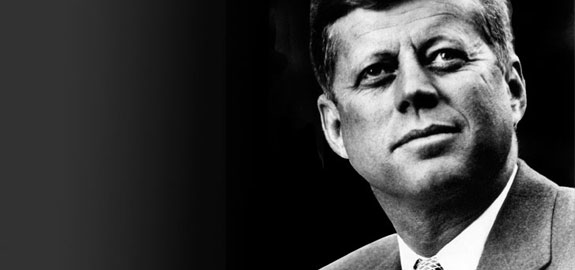

Next week, we will take this idea of arousal and charisma and see how it can affect our perceptions of political leaders. That is, how do times of high arousal (e.g., after a terrorist attack) influence our desire for and impression of charismatic leaders?

Arousingly,

jdt

Damen, F., van Knippenberg, D., & van Knippenberg, B. (2008). Leader affective displays and attributions of charisma: The role of arousal. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(10), 2594–2614.

Pastor, J. C., Mayo, M., & Shamir, B. (2007). Adding fuel to fire: The impact of followers’ arousal on ratings of charisma. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1584–1596.

One Comment

Comments are closed.