How to (Scientifically) Lead a Meaningful Life: Part 1

Every time I find the meaning of life, they change it. — Unknown

Humans, for all eternity, have been seeking an answer to the question: “What is the meaning of life?” And although no empirical data can provide an answer to that question, there has been research on what makes an individual’s life meaningful.

So starting today (and then continuing next week), let’s discuss what it means to live a meaningful existence.

IT BEGINS WITH THE GREEKS

Today, researchers call this concept “meaningfulness.” And although it may sound similar to “happiness,” the two concepts are distinct.

A happy life is one of enjoyment and pleasure, whereas a meaningful life is one of feeling fulfilled or feeling like one has flourished. Importantly, when researchers compare happiness versus meaning in people’s lives, they find the two concepts are related but also distinct.

Happiness tends to come from behaviors that advance one’s own self-interest, whereas meaningfulness tends to come from behaviors that advance others’ interests. Happiness tends to be more fleeting and focused on the moment, whereas meaningfulness tends to be more long-lasting and is focused on the past, present, and future combined. And although happiness is very important to one’s psychological wellbeing, arguably, living a meaningful life is even more important.

So, what actually constitutes living a meaningful life?

IT CONTINUES WITH THREE DIMENSIONS

Researchers have identified three related but distinct aspects of living a meaningful life: purpose, mattering, and comprehension.

Mattering. We are social creatures living in a social world, and to that effect, a meaningful life is also determined by the extent to which we believe our lives are significant, important, and valuable to our social network. This “mattering” also means that we believe our actions contribute to our family, friends, and community–even after our lives are over.

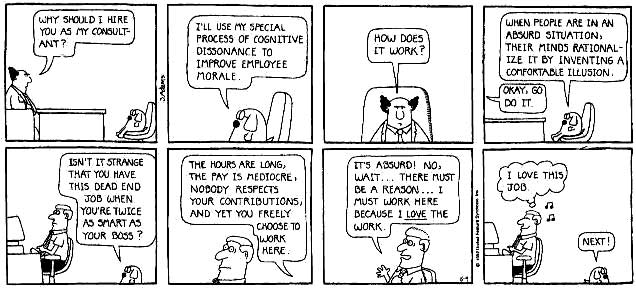

Comprehension. If one believes they live in an unpredictable or uncertain world, it reduces their sense of a meaningful life. Thus, perceiving coherence (i.e., structure and order) in one’s life and the world more broadly is important to living a meaningful life. People need to feel that they understand their place in the world, and that overall, life makes sense.

Altogether, believing that one has purpose, their life matters, and they comprehend the world contribute to believing one leads a meaningful life. And when people don’t believe they have these things, it can result in significant cognitive and emotional deficits.

IT ENDS WITH YOU

In contrast, those who report an absence of meaning in life are more likely to exhibit psychological disorders, are more inclined to suicidal thoughts, and are more likely to suffer from Alzheimer’s disease. And ultimately, those with an absence of life meaning tend to have a premature mortality rate.

So, although you didn’t need this blog post to tell you that meaning in life is important, understanding the factors that contribute to it can better help you achieve it! But, when you have to work, eat, walk the dog, comb your hair, or dust the vents (because that’s very important to your girlfriend), how do you find the time to achieve such meaning?

Next week, we’ll discuss some tips for maximizing your time to maximize your meaning in life.

Meaningfully,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: Take a moment to consider how the three aspects to living a meaningful life (purpose, mattering, and comprehension) fit into your own life. That is, refer back to the descriptions I provided above, and try to identify a factor from your own life–be that a way of thinking, an activity, a person, or anything else–that contributes to each of those dimensions. Once you have that list, see if you can add any other factors to those categories. Then, the next time you’re feeling anxious or depressed, try to bring to mind or even enact one of those factors you listed. You may be surprised to find how simply even reminding yourself of that factor can help restore a sense of meaning and fulfillment to your life.

Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531-545.

Rudd, M., Catapano, R., & Aaker, J. (2019). Making Time Matter: A Review of Research on Time and Meaning. Journal of Consumer Psychology.

One Comment

Comments are closed.