Why Losing Sometimes Feels So Much Worse

Disappointment is inevitable; misery is optional. — Various authors

We’ve all been there. Your favorite sports team loses to their rival. The political candidate you hoped would win doesn’t. A movie you love didn’t get the award.

Everyone feels bummed in these moments—but why do some people seem crushed while others just shrug it off?

The answer might have less to do with what you liked, and more to do with how you thought about your preference.

In recent research that I and my colleague, Richard Petty, published, we examine the following question:

How can two people prefer the same outcome to the same degree, yet react so differently when that desired outcome doesn’t happen?

HOW YOU FRAME IT = HOW YOU FEEL IT

Let’s start with a simple concept from psychology known as “framing effects.”

Framing effects mean that the way something is described can change how you feel about it—even when the facts stay the same.

Take this example: If someone says a drink is “80% sugar free,” it sounds healthier than saying it’s “20% sugar,” even though the two statements mean the same thing.

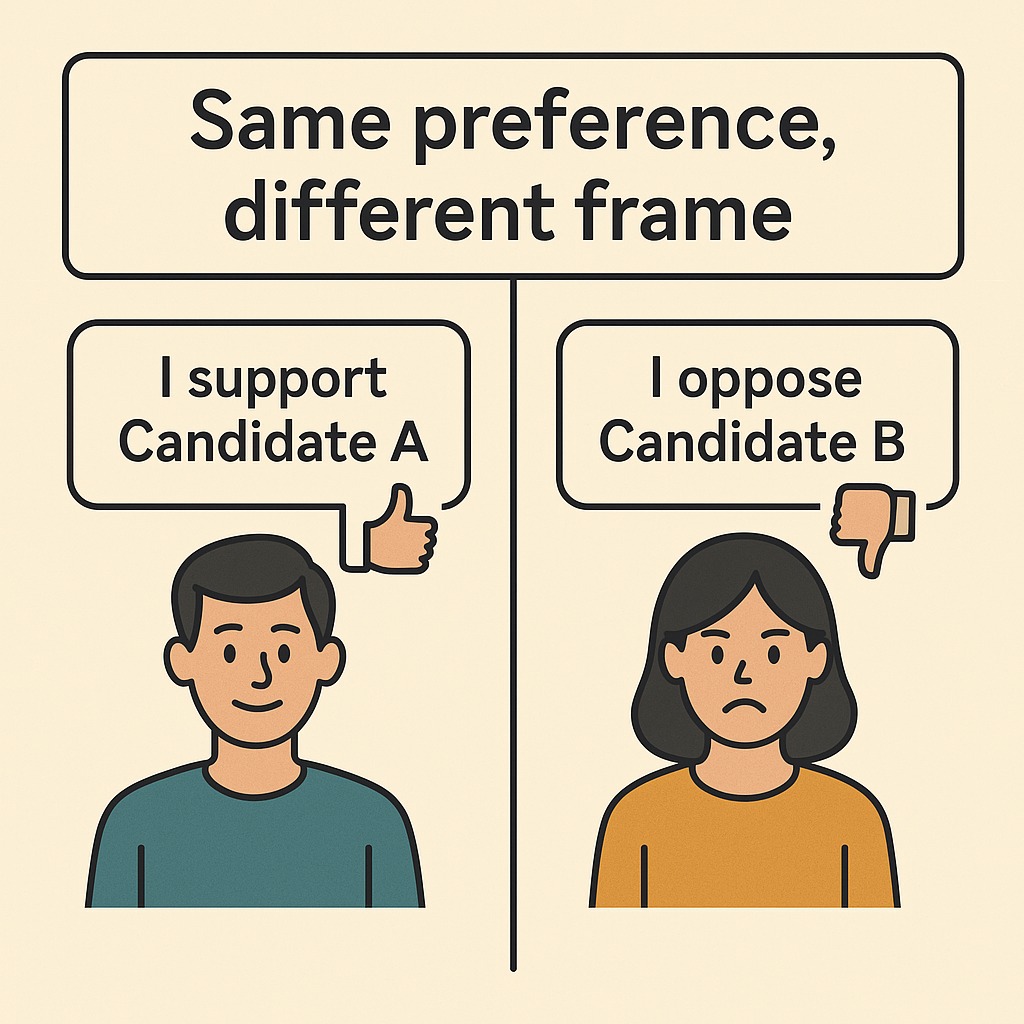

In my research, we study a specific type of framing effect known as support-oppose framing.

Imagine two friends who both prefer Candidate A over Candidate B. However, one might say, “I support Candidate A.” The other might say, “I can’t stand Candidate B.” In both cases, people prefer Candidate A. They just frame that preference differently.

One person frames their preference in terms of support, the other in terms of opposition.

It turns out, this difference in framing can change how you feel if things don’t go your way.

THE OPPOSER’S LOSS EFFECT

In a series of 16 studies involving over 12,000 people, we found a robust effect.

People who thought about the exact same preference in terms of the option they opposed (vs. supported) felt worse when things didn’t go their way. This pattern showed up in sports, politics, health, finance, shopping, and more.

We called this phenomenon the opposer’s loss effect.

For example, in one study we had people frame their preference for getting the flu vaccine either in terms of wanting to stay healthy (support) or not wanting to get sick (oppose). Later, we had them imagine they caught the flu. People reported being more upset if they framed their preference in opposition (vs. support).

In another study, we had people choose between two couponing apps to download. They made their choice either thinking about the one they opposed or the one they supported. Afterward, whichever app they chose, we revealed negative information about it. Once again, those who framed their initial preference in opposition (vs. support) reported more negative reactions to the undesired outcome.

We found this effect in people’s social media posts on Twitter (now X), over long periods of time, and even in 20 years worth of people’s reactions to U.S. Presidential elections!

EXPLAINING THE EFFECT

So, what’s going on here?

In any preference, there are often pros and cons to either option. Even if you really prefer one option, there might be some good things with the other side.

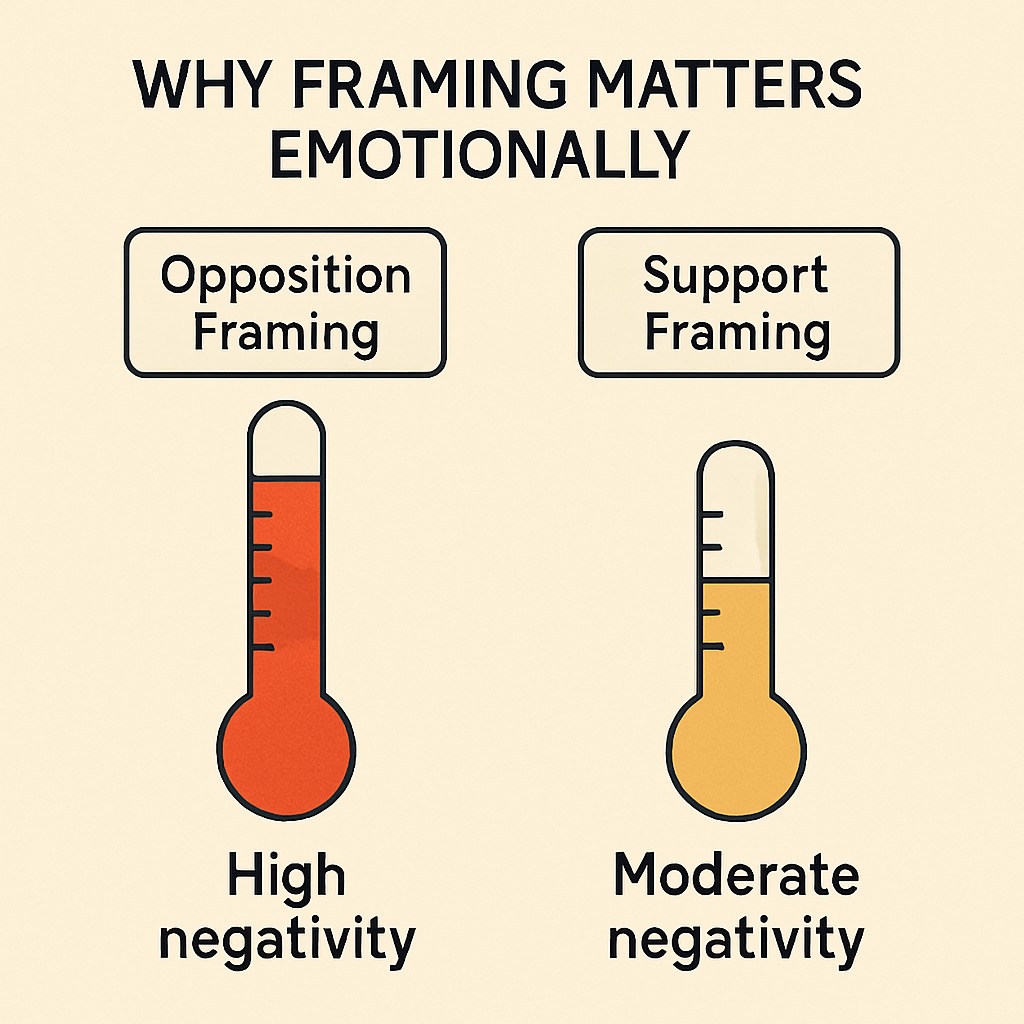

When you frame your preference in opposition, however, you’re less willing to admit to those positive things in the non-preferred option. So, when the bad news does come, it makes it much harder to see the silver lining.

In other words, when we see things in black-and-white—good versus evil, right versus wrong—losing feels like a total disaster. And when you frame a preference in terms of opposition (vs. support), you’re more likely to see your preference in this black-and-white thinking.

Supporters, on the other hand, still feel bummed when things don’t go their way. But because they were focused on what they liked, they tend to feel less crushed when they lose.

A TRICK TO FEEL BETTER

If there’s one thing to take away from this research, it’s this:

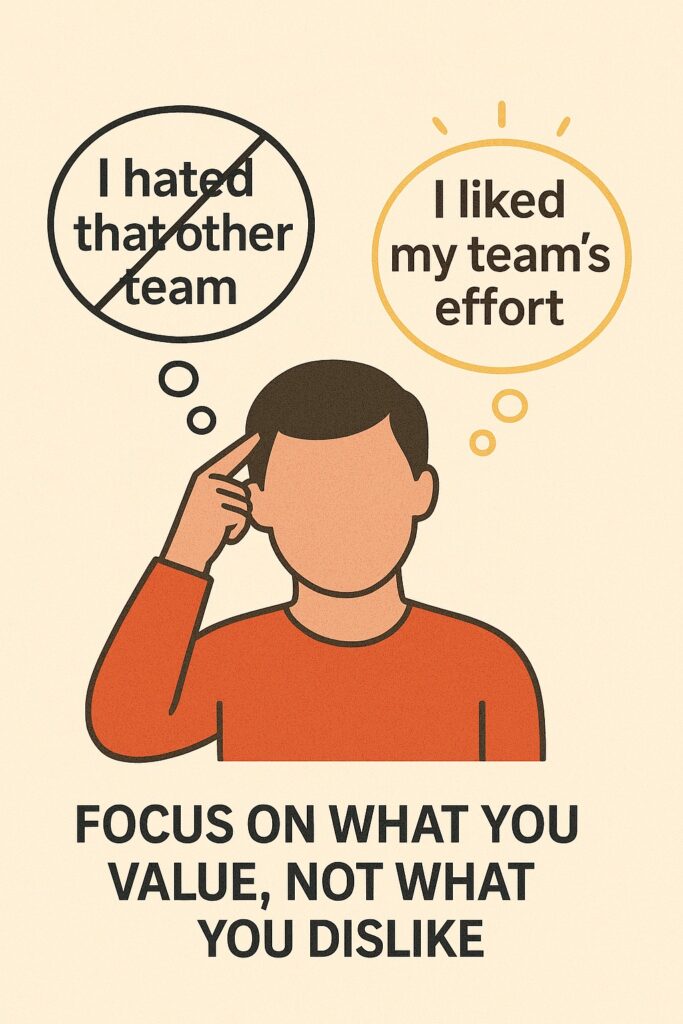

If you’re feeling upset about something not going your way, try to focus on your reasons of support for the preferred option.

Instead of saying, “I hated that other option,” try thinking, “I liked my choice because…” and fill in the blank. Maybe you admired your team’s teamwork. Maybe you appreciated your politician’s honesty.

By focusing on what you supported—rather than what you opposed—you might not be as disappointed if things don’t turn out the way you hoped.

Supportively,

Jake

Everyday Psychology: Want to know a little more about the background on this research? It started in the second year of my Ph.D. program, meaning it took over ten years to finally get published. In fact, it was rejected by four different journals before finally landing at one of the most prestigious psychology journals. To find that perseverance, I took the advice of my own work. After each defeat, I focused more on what I liked about the paper and less about what I disliked in the review process. Keeping this support-based frame helped to dampen my negative reactions (and let me tell you, they were negative) after each piece of disappointing news, helping me stay motivated.

Teeny, J. D., & Petty, R. E. (2025). Reactions to undesired outcomes: Evidence for the opposer’s loss effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000436