Do We Feel the Same Emotions?

I am human; therefore, nothing human can be alien to me. – Terrence (the slave turned Roman playwright)

Sometimes when speaking to others, the monumental illogicality of their words almost necessitates they came from a different culture. Like seriously: How could anyone ever dislike peanut butter?

But beyond these more superficial differences between cultures—the clothes, the customs, their toppings for jelly sandwiches—there are some components of the human condition that seem universal. That is, regardless of one’s societal upbringing, there are certain things all humans experience:

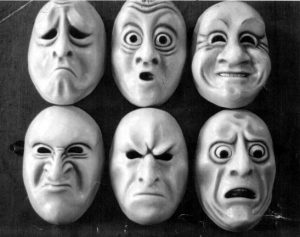

Love. Anger. Happiness. Sorrow.

Regardless of flag you salute, your emotions, how you feel and hurt, should be understood across borders. For example, if one person lives in Africa, the other in Antarctica, both will still feel distress over the season five finale of Game of Thrones.

But is this really true? Do people from opposite ends of the world really feel the same emotions? As with seeing colors, is that pigment of blue really the same hue for two people? Or just the same name?

In examining this question of emotions, researchers asked U.S. and Japanese participants to recall and write down a pleasant, personal memory. In doing so, they were instructed to elaborate on the emotions they felt during the event.

Analyzing the responses, the researchers found that when describing a pleasant event, Americans wrote predominantly about positive emotions. However, the Japanese wrote more mixed appraisals. That is, rather than this pleasant memory containing only “pleasant” emotions, they expressed feeling both positive and negative.

So why would this be?

As you’re probably aware, one of the large cultural differences between Western and Eastern countries is their focus on individualism versus collectivism. Whereas westerners are much more individualistic (i.e., focused on personal success and accomplishment), easterners are much more collectivistic (i.e., focused on their group’s success and accomplishments).

When recalling the pleasant memories, U.S. participants were much more attuned to their own emotions and the pleasure that this event brought to them individually. With the Japanese, yes, they recognized their own pleasure in the matter, but they also considered the “costs” it brought to other people.

Furthermore, Eastern countries (compared to Western ones) tend to engage in more “dialectical thinking.” That is, they are more comfortable with contradiction or holding opposing views at the same time. In this regard, then, although having both positive and negative emotions may make the event no longer seem pleasant to westerners, for others, such a paradox of emotion is natural.

Thus, it may seem like something as instinctual and fundamentally definitional as emotions would be less subject to the effects of one’s upbringing; however, even this can be influenced by one’s environment.

Next week, we’ll talk more about emotions–a post that is sure to astonish you. Or make you excited. Or astonish, excite, depress, and tire you. Oh, who knows what emotions you’ll feel. But you’ll enjoy them.

Emotionally,

jdt

Miyamoto, Y., Uchida, Y., & Ellsworth, P. C. (2010). Culture and mixed emotions: co-occurrence of positive and negative emotions in Japan and the United States. Emotion, 10(3), 404.

Love your posts Jake!

I’m glad you enjoy them, Patty! Thank you for reading!