Becoming More Moral

It is not who is right, but what is right, that is of importance. – Thomas Huxley

I have been going around citing a quotation recently (no, not that one above), that may in fact be made-up. Although devising things to impress others is not new to me (in the form of short stories, mind you, not outright deception), I really want this quote to be real.

Or maybe I don’t so that I can copyright it and put it on t-shirts and bed sheets.

So what is it?: “When you have knowledge of what’s right, you do what’s right.”

That is to say, when you have a decision in front of you and there’s one choice you want to do, but know is not the rightest thing to do, the fact that you still desire it means that you don’t really know that it’s right not to do it.

For example, let’s say my friend has a car that I really want to drive, and when he leaves for the weekend, I consider borrowing his keys to take for it a spin. Now, although I know it’s “wrong” to drive his car without his permission, I still want to drive it.

However, if I truly knew the right thing to do was not drive it, that is, I stopped thinking things like “Well, if he doesn’t find out…” then I would know that not driving it was the right thing to do and no longer even consider it an option.

I could still desire to drive his car, but the thought of driving it without his permission has been removed from my mind as a possibility—because I actually know that doing so is the wrong thing to do.

But coming to that realization can be very, very difficult. Fortunately, researchers have studied ways to make people “more moral.”

In one of these studies, experimenters had participants write a letter to themselves: either to themselves one week in the future or five years.

Interestingly, those who wrote to themselves farther in the future were more moral on a number of measures, such as intended behavior to do good things as well as their responses to moral vignettes.

In a second study, researchers digitally uploaded a picture of the participant’s face onto an animated character and then gave them a virtual reality headset, letting the participants wander around a house until they ended up in front of a large mirror.

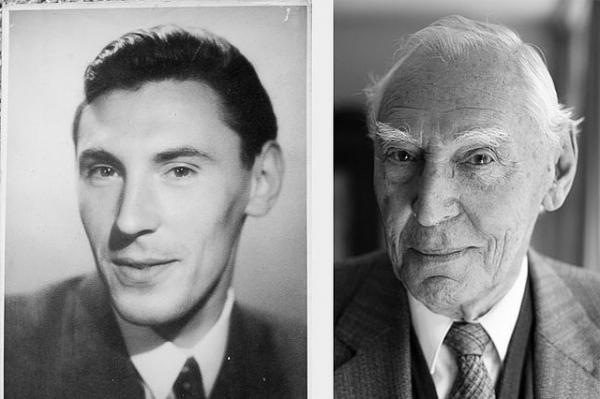

Now, for some, they simply saw an animated version of themselves, their reflection mimicking the movements in the real world. However, the other half of participants saw an older version of themselves, one with digitally added wrinkles, gray hair, etc.

And just as writing a letter to yourself farther in the future makes you more moral, so did seeing yourself as an older individual.

The idea, here, is that imagining yourself older helps you focus on the important things in your life—like staying true to your word and considering who you want to be as a person: thoughts that encourage more moral behavior.

This is why I’m always looking at myself in the mirror. You know, because I’m visualizing an older Jake to facilitate moral behavior.

…“Right”…

Elderly,

jdt

Society for Personality and Social Psychology Conference (2014). Current directions in the study of Character: The four W questions (what, when, why and where). Symposium S-E5. Austin, TX