How to Catch a Hypocrite

Every person alone is sincere. At the entrance of a second person, hypocrisy begins.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson

There are few things in life more frustrating than a hypocrite. Well, actually, I can think of one.

A hypocrite who refuses to admit they’re a hypocrite.

So, what do you do in these circumstances? How do you help someone change (or at least recognize) their inconsistent ways?

Today, let’s learn “how to catch a hypocrite” using research on the psychology of hypocrisy.

A HYPOCRITE OR NOT A HYPOCRITE?

In the broadest terms, hypocrisy is defined as a “word-deed misalignment.” Or put another way: a person says one thing but then does the opposite. For example, a housemate who says they want the house clean but then leaves dirty dishes in the sink.

But inconsistency alone doesn’t make someone a hypocrite.

For example, if an introvert says they never go to parties, but then attends one, would you call them a hypocrite? Or if a person says their favorite ice cream flavor is vanilla (really, vanilla?) but then eats chocolate, what about this?

So, to determine whether someone is really being a hypocrite, you have to determine whether they hold an “evaluative standard” on the topic.

A famous way to describe hypocrisy is “not practicing what you preach.” An evaluative standard, then, is this “preaching.” Or in other words, believing their opinion on a topic is “right” or “correct,” and those who disagree are “wrong” or “bad.”

To highlight the importance of evaluative standards in hypocrisy, consider one study where researchers had participants evaluate two different targets, both of whom cheated on an academic test.

In one case, the cheater just believed cheating was bad personally (no evaluative standard), whereas the other cheater looked down on others for cheating (yes evaluative standard). For the first target, fewer than half of all participants rated him as hypocritical. However, for the second target, it was over 90%!

This is why moral inconsistency is often seen as hypocritical. For example, if a marketer thinks sexualization in advertising is morally bad (but then later uses sexualized advertising), they’re seen as VERY hypocritical. However, if a marketer thinks it’s economically unwise to use sexualized ads (but then later uses them) they’re seen as less of a hypocrite.

Moral beliefs naturally carry an evaluative standard with them. That is, if you hold a belief morally, you think that belief is right and those who disagree are wrong. So, it’s automatic hypocrisy when you violate one!

To sum it up, hypocrisy means the person must (1) exhibit some kind of word-deed misalignment, and (2) hold an evaluative standard on the topic.

AH HA! I GOT YOU NOW!

Now that we can properly identify hypocrisy, how do we best call someone out for doing it?

First, it’s important to realize that being called a hypocrite is not a good feeling. So, calling someone a “hypocrite” will make the other person defensive and less likely to change. Therefore, don’t even use the word “hypocrisy” or “hypocritical” when dealing with the person.

Instead, your whole approach to the conversation should be through question-asking. Rather than making accusations, try to ask him or her questions about their behavior. Specifically, you want to begin by asking them questions that get them to state the relevant evaluative standard.

Whether the person was being hypocritical about environmental behaviors, social kindness, a religious belief, whatever, you want them to self-express what they think is the “right” stance to hold on the topic. In other words, you want them to acknowledge their evaluative standard.

After this – and again through question-asking – you want them to acknowledge the specific instance (or even two or three) where they acted in conflict with this belief. For example, if you just had them establish that it’s “important not to be on your phone when hanging out,” you might ask them: “Weren’t you just using your phone a little bit ago, though?”

Naturally, the person will try to justify why this instance of inconsistency isn’t hypocrisy. So, try to describe to them how “an outsider” would view their behavior as a violation of their own evaluative standard. Importantly, though, try not criticize them for this hypocrisy. Instead, explain to them why their inconsistency frustrates or hurts you.

For example, you could express how their behavior makes you feel like you’re less able to trust them or take them at their word, which makes you feel sad. Focusing the emotional consequences on yourself (or even other, relevant people) should help motivate them to acknowledge their hypocrisy and improve in the future.

SOMETIMES IT STILL DOESN’T WORK

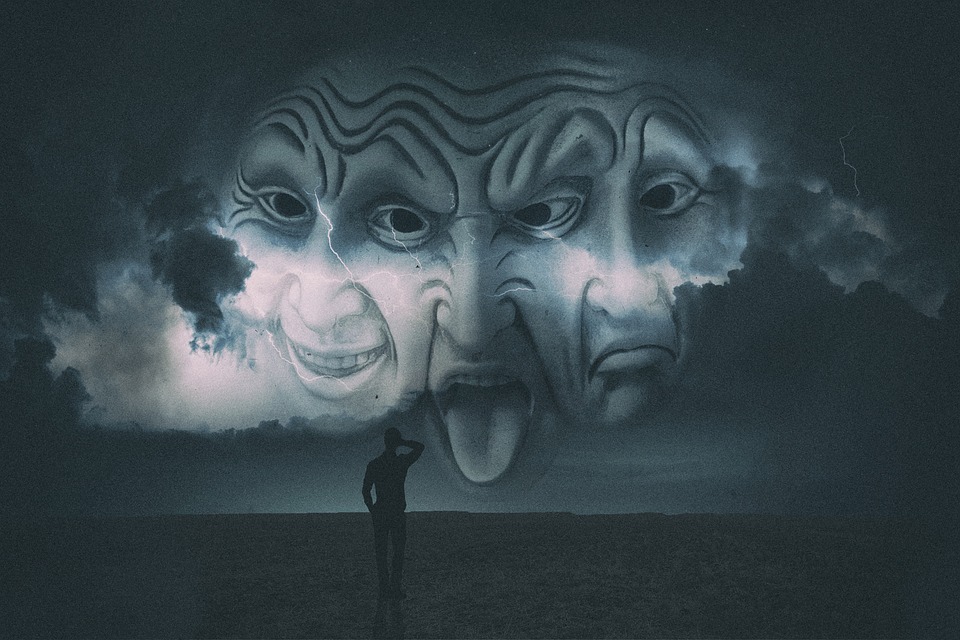

It’s important to note that after people’s hypocrisy is pointed out to them, this inconsistency will automatically create internal, psychological discomfort (what’s referred to as cognitive dissonance). To deal with that discomfort, it will be easiest for them to simply try to “explain it away.”

So, try to be patient. And calm. If this is something that’s important to you, it might take a couple instances of pointing out their hypocrisy in a neutral manner before it finally registers with them.

It is worth noting that you should be careful about trying to “catch them” in front of others. Although it can sometimes be helpful to have others reaffirm your perspective, hypocrites are less likely to admit being hypocritical the more people they have to admit it to.

Unhypocritically,

Jake

Everyday Psychology: In general, people tend to judge themselves based on their intentions, while they judge others based on their actions. For example, someone who is running late to a meeting may think it’s okay because they had a good reason, such as traffic or a family emergency. However, if someone else is late to the same meeting, the person may judge them harshly without considering their reasons. With hypocrisy, be prepared for hypocrites to justify their actions through their intentions. Point out that regardless of their intentions, their actions still had consequences and that’s what matters.

Alicke, M., Gordon, E., & Rose, D. (2013). Hypocrisy: What counts? Philosophical Psychology, 26(5), 673–701. Doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2012.677397

Kreps, T. A., Laurin, K., & Merritt, A. C. (2017). Hypocritical flip-flop, or courageous evolution? When leaders change their moral minds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(5), 730–52. Doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000103