The History of Humans

Man still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin. —Charles Darwin

Today, I left for San Antonio to attend the annual conference for the Society of Personality and Social Psychology, where I (my mouth still speckled with BBQ sauce I’m sure) will engage with the research of thousands who are trying to understand and explain human behavior.

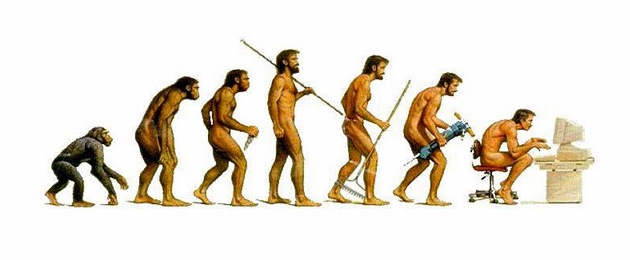

But to really see the “why” behind what humans do, we have to turn to our roots as wild-born animals and see what drove them to get us where we are today.

Life, in a biological sense, began on this planet about 3.8 billion years ago, but it wasn’t until 2.5 million years ago that humanoid creatures like ourselves emerged. And 500,000 years after that [and we think a three-hour movie is an unbearable length of time], did these humanoids begin to spread from Africa to the rest of the world.

Now, as evolution works, when these humanoids broke off into different areas of the planet (some traversing to Europe, others Asia, some remaining in Africa), they developed into different species.

For example, just as there’s the grizzly bear, the Kodiak bear, and the panda bear, so, too, did there develop Homo neanderthal, Homo erectus, and us, Homo sapiens. In fact, about 100,000 years ago, scientists have confirmed that there were at least six different species of humans populating the earth concurrently.

That is, although Homo sapiens emerged as the sole and dominant humanoid, it very well could’ve been Homo neanderthal that overtook the earth–or we could still have multiple species of human populating it today.

Now, in our primitive stages as Homo sapiens, we were nothing spectacular on this planet. In fact, at that time, our position in the food chain was “solidly in the middle.” For example, our first stone tools were developed to crack open the bones of carrion (i.e., dead animals other creatures had killed), because by the time we were able to forage the animal for food, all that was left was the marrow inside the bones.

Now, in our primitive stages as Homo sapiens, we were nothing spectacular on this planet. In fact, at that time, our position in the food chain was “solidly in the middle.” For example, our first stone tools were developed to crack open the bones of carrion (i.e., dead animals other creatures had killed), because by the time we were able to forage the animal for food, all that was left was the marrow inside the bones.

However, for reasons that remain in mystery, humans made a sudden leap in their cognitive abilities. That is, we went from stone tools, hunting small animals and working in small groups, to much more advanced tools, hunting large game, and working in much bigger numbers.

Researchers call this the Cognitive Revolution, and we only have vague and incomplete clues to how it came about.

For example, human’s discovery of using fire to cook allowed us to devote more energy to our brains. That is, whereas a chimpanzee takes five hours to chew and breakdown raw food, by cooking it, humans are able to eat and digest it in 1/5 the time. This then allowed humans to have shorter intestinal tracks, rerouting that use of energy to our brains for increased cognitive capacity.

But regardless of how we made this sudden and unexpected leap in cognitive prowess, it had some significant (and devastating) effects on the ecosystem–as well as our own psychology.

With all other instances of evolution, such advancements happen gradually. For example, as bears evolved into better killers, in response, fish evolved into be better swimmers, and deer evolved to become more skittish. Because evolution typically happens over long periods of times, everything in an ecosystem can advance in synchrony such that no one animal throws off the balance.

Furthermore, this rapid development from the middle of the food chain to the very top had some traumatic effects on our own psychology, impacting the ecosystem even more. Although we still had the fears and anxieties of a creature in the “middle of the predator lineup,” we now had the power to destroy anything that frightened us. This “undue” paranoia, then, led to the mass killing of animals and harvesting of plants as we still maintained our primitive, forager concerns.

However, so far, I’ve only told of how humans in general (i.e., the six independent species) developed in unison. Next week, we’ll talk about how Homo sapiens took over more than just the other furry and fanged creatures, but also their own kind.

Humanly,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: Some researchers have claimed that all art, sports, hobbies, etc. are complex “mating rituals” developed from our earlier, evolutionary selves. Looking at your own behavior, how could you translate your own anxieties, goals, efforts into complex versions of the same anxieties, goals, and efforts our primitive selves would have had?

Harari, Y. (2016). Sapiens. Harper Collins Publisher. New York, Ny.

Fascinating. I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article and would love to see more.

I’m glad you enjoyed it! If so, there’s a part two on the site, too:

https://everydaypsych.com/history-humans-pt-2/