The Trick to a Super Memory

Time moves in one direction, memory another. – William Gibson

If you haven’t heard me complain about my big and impending candidacy test (the three-part exam that determines whether I’m “worthy” to pursue a PhD), then you have that opportunity now:

Ah! I have a huge test—that covers everything in social psychology!—in just over a week!

But in order to study and memorize all the information for it, I do what any good student does and turn to the ancient Romans. So first, a bit of a history lesson.

There was once a poet and wise man by the name of Simonides (556 – 468 B.C.) who was invited to perform poetry at a grand banquet in Thessaly. With the meal concluding, and his performance approaching, he stepped outside to get some air and practice his verses.

However, when he did, the roof to the banquet hall collapsed, killing dozens of people seated around the hall. In attempt to identify the mangled bodies (as was necessary for Roman burial traditions), Simonides noticed an odd thing:

He could recall almost everyone’s exact location at the various tables. And although grim, this incident prompted Simonides to develop the mnemonic the method of loci.

A mnemonic is typically thought of as a mental “trick,” like making an acronym out of topics, to help remember something. And in ancient Rome, where papyrus was rare, mnemonics were used quite readily for orations of any kind.

However, over the years, most cultures have abandoned their use—for reasons, honestly, I cannot understand.

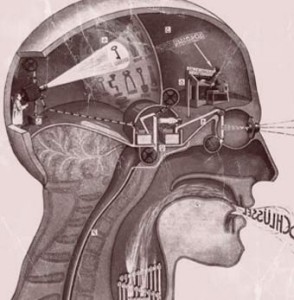

The method of loci (arguably the most useful) essentially relies on two things for which human memory is evolutionarily predisposed: the recollection of geography and images.

Now, mentally walk forward in your structure, create another image for what you want to remember, and then place it, too, at a significant location. Continue walking through, positioning images till you’ve outline all you need to know.

For example, let’s say for my big test I need to remember the citation (Briñol & Petty, 2004) which discusses the role of meta-cognitive confidence in persuasion. Because I know what both those researchers actually look like (they’re two of my advisors), and I know the study involves the use of head nodding to manipulate confidence, I imagine both my professors as bobble-head dolls, place them at my front door, and then move on to the next citation.

(To recall the year, I have previously committed numbers to memory, e.g., 1 = gun; two = glue; three = bee; etc., so I just incorporate those images into the one with the bobble-head.)

Many people are turned off of this method because they think they have to remember even more things, but the brain was designed to recall images like this (the weirder, the better), and if you try it, you’ll find it improves your memory dramatically.

In two days, I’ve already memorized 120 citations, and now, I only have 380 left to go. Whether or not this will actually help me on my test…? At least I’ll impress my professors with my memory.

Memorably,

jdt

Maguire, E. A., Valentine, E. R., Wilding, J. M., & Kapur, N. (2003). Routes to remembering: the brains behind superior memory. Nature Neuroscience, 6(1), 90-95.

Ross, J., & Lawrence, K. A. (1968). Some observations on memory artifice. Psychonomic Science, 13(2), 107-108.