Becoming an Expert at Anything

An expert is one who knows more and more about less and less. – Nicholas M. Butler

Based off of research by Anders Ericsson, Malcolm Gladwell made famous the idea that it takes a person 10,000 hours of practice to become an “expert” at something. Although this claim has been challenged, I think we can all agree that becoming an expert at basketball, in wine tasting, on the battlefields of World of Warcraft, or any other activity/area of knowledge takes a lot of time.

Or does it?

TWO TYPES OF EXPERTS

When researchers talk about experts, they have to talk about two different kinds: those with subjective expertise and those with objective expertise.

For example, to find out how much subjective expertise you have, I could simply ask: “On a scale of 1 – 10, how expert are you at Jelly Bean flavors?” If you respond with a 9 or a 10 (regardless of how much knowledge you actually have about this candy), you would qualify as having high subjective expertise.

On the other hand, if I laid out ten Jelly Beans and asked you to blindly identify as many as you could, we would have a test of objective expertise. (Spoiler, they’re all ear wax flavored.)

For example, sports fans who highly identify with a team may express high subjective expertise, even though they don’t have any actual knowledge. That is, because it feels so personally familiar to them. On the other hand, after watching a sports team for a long time, you start to gain objective expertise about it while you simultaneously begin identifying with it.

Although people probably assume that if you have high subjective expertise when you actually don’t have any objective expertise, it’s no good. But actually, having high objective experience can lead to similar issues. For example, research shows that those who have high objective expertise about allergy medicines, spend less time reading about new products, thinking they already know enough. When in fact, they actually miss some pretty substantial changes!

THE DUNNING-KRUGER EFFECT

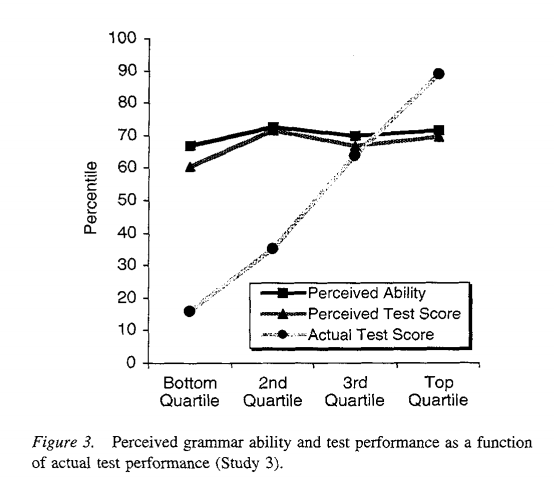

In one of social psychology’s most famous (nerd famous) studies, participants came into the lab and answered SAT grammar questions. Afterward, they ranked themselves on how well they thought they performed compared to others.

The researchers showed this same pattern of effects when they gave logical reasoning tests and even a humor test. In other words, when someone has a terrible sense of humor, you can suspect they still think they’re funnier than average.

The researchers assert that being inexpert at something not only makes someone bad at that task, but it also makes them unable to recognize they’re bad at it.

GATED LEARNING

So you’ve read this far and you’re starting to think: “Jake, from your title, I thought you were going to teach me how to become an expert.” Fear not. There are still 217 words left from the total count I allot myself for these posts (otherwise, I could write forever…)

First, there’s the “analytic stage.” Here, you learn the relevant and important terms as well as the general rules for how to think about it. For example, with wine tasting, you first to learn the language to describe what you’re tasting (e.g., the “tannins”), then you learn where to focus your attention: the aroma, taste, and finish. Then, once you have more of this down, you go to the second stage, the “holistic stage.”

At this point, it’s you’re goal to take more of a comprehensive approach to the indulgence. Think of how it all comes together as one unique flavor. In fact, the research I’m referencing (Latour & Deighton, 2018) even had participants drawing a picture of what they tasted and even give a narrative to the experience. In fact, in this research it actually helped wine ‘enthusiasts’ better recall and identify which wines they had tasted.

Even still, you know an easier way to become an “expert?” Just give a 9 or 10 when you’re asked: “How much an expert are you?”

Expertly (Subjectively? Objectively?),

jdt

Everyday Psychology: A recent study that has gained some media attention has shown that people who tend to believe in conspiracy theories are less likely to trust the opinions of experts–which is probably not a good thing. However, to combat conspiracy thinking we have to know more. For example, is it that conspiracy minded people don’t trust any “expert?” Or is it a specific kind of expert they don’t trust (e.g., academics)? Or is it that to the conspiracy minded, the experts are only those who support the conspiratorial beliefs themselves? Although all of these possibilities would result in the same outcome (i.e., those with a conspiratorial mind don’t trust the opinions of established experts), understanding why they don’t trust them is necessary to helping correct their mistaken beliefs.

Latour, K. A., & Deighton, J. A. (2018). Learning to Become a Taste Expert. Journal of Consumer Research.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of personality and social psychology, 77(6), 1121.

Wann, D. L., & Branscombe, N. R. (1995). Influence of identification with a sports team on objective knowledge and subjective beliefs. International Journal of Sport Psychology.

Wood, S. L., & Lynch Jr, J. G. (2002). Prior knowledge and complacency in new product learning. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(3), 416-426.