Happiness Hangovers

Don’t cry because it’s over, smile because it happened. — Dr. Seuss

But, like a birthday or a wedding or even a great weekend, that acute and abundant happiness from the holidays quickly brings on the blues once it goes away.

In other words, we experience what’s called a ‘happiness hangover.’

OPPONENT PROCESS THEORY

On the surface, it doesn’t really make sense that we would experience happiness hangovers (i.e., feeling down or depressed after having a very positive experience or set of experiences).

Now, let’s say something really positive happens to you (e.g., you open presents on Christmas day), and your feeling-state increases to a ‘+5.’ Now, once you’ve opened all those presents, you should return to a feeling-state of ‘0’ if not something slightly positive like a ‘+2.’

Instead, after the thrill has subsided, we actually end up in a negative feeling-state (e.g., a ‘-2’). But, if nothing negative has actually happened, why do we feel negative rather than just return to neutrality?

According to opponent process theory, when the body becomes physiologically excited (e.g., when you get really happy), a simultaneous process activates to counteract this excitement. That is, if the body were to keep getting more and more excited, it would become too activated. (Think of drinking too much coffee.)

To prevent this over-excitement, the nervous system simultaneously triggers a “deactivating” or depressing process in the body to balance out this “activating” or exciting process.

Worth noting, this deactivation process is a lot slower and weaker than its activating counterpart. That’s why we still feel happy when we get excited. However, once the source of the excitement disappears (e.g., you’re no longer opening presents), that activating process starts to decrease while that deactivating process starts to increase.

THE THEORY IN ACTION

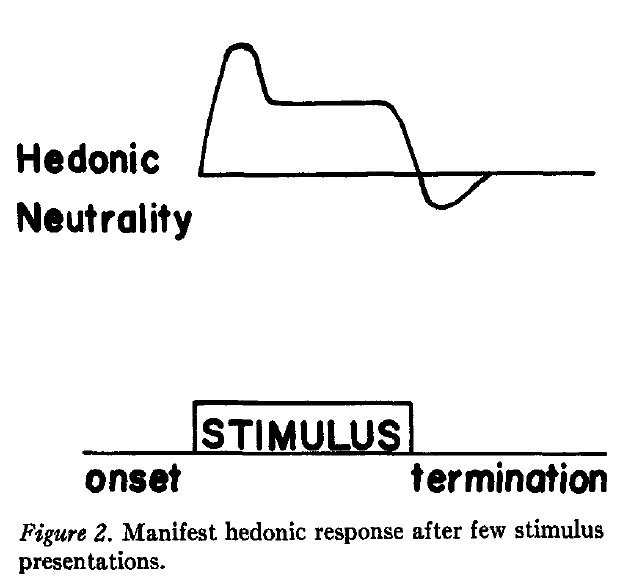

If you see the graph below, when the excitement/good time initially happens, one’s happiness peaks. However, as the source of that happiness is removed, that simultaneous, deactivating process takes over, trying to get the person back to a state of normalness (i.e., homeostasis) by reducing their excitement.

These opposing forces—the initial, dominant one and the weaker, opponent one—then work in tandem to try to bring a person back to balance/homeostasis. Again, though, because the dominant process (e.g., excitement after opening presents) depends on the source, once the presents end, so does that process.

On the other hand, because the opponent process happens within the body, it keeps on working even after the source has ended—which leads to the ‘happiness hangover’ we’re all so familiar with.

Interestingly, you can even see these effects happening in the opposite direction.

For example, let’s say you have a really negative experience (e.g., your brother beats you in a game of Catan). This may move my neutral feeling-state from a ‘0’ to a ‘-3.’ However, at the same time this negative agitation occurs, a simultaneous process begins to “deactivate” it.

Now with the holidays, you’re probably experiencing life as I first described it: with a happiness hangover. However, the good news is that your body will stabilize after a little more time, and you’ll return to that very comfortable feeling-state of neutrality/homeostasis.

If you want to speed up that recovery process, though, check out this week’s Psych·o·philosophy to Ponder 😉

Hungover,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: Feeling a little down with the holiday celebrations mostly behind us? To help combat those blues, I have two primary suggestions. First, consider engaging in some mindfulness practice (i.e., practice mediation by engaging in non-judgmental thinking while focusing on the present moment). As an added tip, try this mindfulness practice in the shower, where you’ll have that pleasure of hot water to focus on. Second, practice giving gratitude for what you have. Gratitude is one of the most powerful practices for improving one’s mood, and will be particularly helpful here. That is, rather than focusing on all the fun you’re no longer having, it helps you focus on the great fun you already had.

Landy, F. J. (1978). An opponent process theory of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(5), 533.

Solomon, R. L. (1980). The opponent-process theory of acquired motivation: the costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain. American psychologist, 35(8), 691.