The History of Humans Pt. 2

But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought. — George Orwell, 1984

Language is powerful. Probably more powerful than you think. For although “sticks and stones can break bones,” words can topple nations. It is language that provides the basis for record keeping. It is language that allows us to have laws that govern society. It is language that grants us the ability to hold ideologies and beliefs that guide our very lives.

But for as much power as language has today, it had even more power during humanity’s formative years. In fact, it was the development of language that allowed humans to begin their eventual and total conquest of planet Earth…

Before complex language developed, humans—like many other animals—were still able to communicate with one another. For example, green monkeys today have different warning calls to signal when an encroaching eagle poses a threat compared to when a lion does.

But in contrast to the dexterity of humans’ language today, this level of communication is relatively unremarkable—primarily, because it can only communicate about the here and now.

For example, imagine if green monkeys were able to tell other monkeys that earlier in the day, they had seen a pack of lions roving near the water hole and looking to head east toward the monkeys’ encampment. Or in other words, what makes human language so powerful is that we can describe things that aren’t happening right in front of us.

But in order to communicate something like the above example, one’s language needs to be vastly complex. With the simple hypothetical sentence I provided, the monkeys would have to have words to signal time, words to signal very specific locations, and words to communicate the intentions of others.

And before 70,000 years ago, no creature on this planet had that ability. However, as we discussed last week, for whatever reason (probably dumb luck), a neural mutation occurred inside the brains of Homo sapiens, spurring this Cognitive Revolution which allowed them to speak about and describe their world in blazing detail.

And with this development of language, humans were able to do something astounding: create fictions.

In order to talk about the past or the future (e.g., “that cave had snakes in it;” “we will see the deer in the meadow”), you have to be able to imagine a world that doesn’t technically exist. And when you’re able to do that, an infinite number of “worlds” suddenly opens up to you—worlds that don’t only exist in the mind of one creature but worlds that can exist in the minds of multitudes.

For example, chimpanzees typically live in groups of no more than a few dozen. In order for this “troop” to function, they have to have a hierarchy in which they understand who are the leaders and who are the followers. But without complex language to describe the relationships and power statuses of fellow chimpanzees, having too many chimpanzees in the troop destabilizes the social order.

Think of this: “In a band of fifty individuals, there are 1,225 one-on-one relationships, and countless more complex social combinations” (Harari, p.23). Thus, the only way for massive groups of animals to work together is to have fictions (i.e., beliefs you can’t “see”) that bind multitudes to the same goals.

Be that the “fiction” of a nation-state, an ideology, a religion, or a set of laws, without a language that allows you to create beliefs bigger than what’s in front of you, there’s no way to attain social order within massive groups of people.

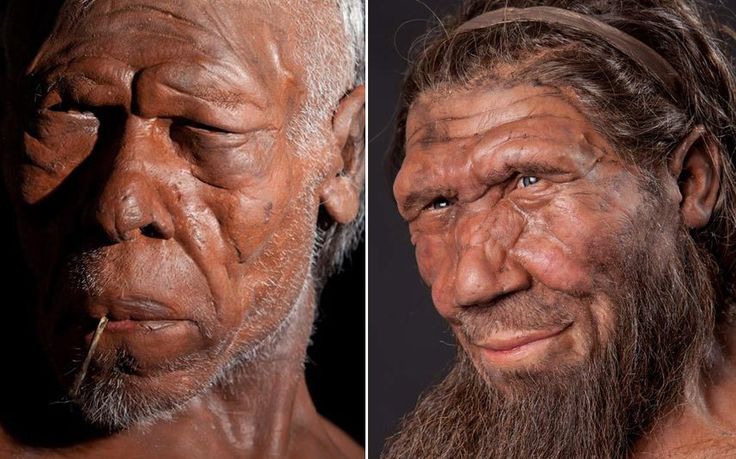

Now, if you remember from last week, Homo sapiens were only one of multiple species of humans populating the earth thousands of years ago. But for whatever reason, they were the only one to gain this cognitive access to complex language.

And today, that language is the reason they’re the only species of human still occupying it.

In fact, 100,000 years ago, before this Cognitive Revolution, researchers have evidence of a skirmish between migrating Homo sapiens and the Homo neanderthalensis living in the Middle East. In this encounter, however, the Neanderthals actually beat back the Sapiens and the Sapiens retreated to their homeland in Africa.

However, about 30,000 years later, as Sapiens suddenly gained access to this complex language, they were able to take their meager tribe of less than a hundred and turn it into a legion bound by fictions. So, when they next encountered the puny Neanderthal tribes—and all the other species of humans for that matter—that massive army of Sapiens would be the last to witness their genetic cousins as they wiped every last one of them off the Earth.

In these last two posts on the history of humans, I barely covered the first chapter in the recently released book, Sapiens. So if you have at all been intrigued by how humans of today evolved from our great-great ancestors, I highly recommend you purchase and read the book for yourself. It’s amazing to see how our psychology of eons ago still plays out in our psychology today.

Humanly,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: When people think of laws, religions, or even ideologies like equality as “fictions,” it often arouses a sense of anger, disbelief, or rejection. But think on that for a minute. Would you ever be able to teach a chimpanzee that it has a right to a fair trial? Would you be able to promise a chimpanzee a predator-free afterlife if it refrained from flinging poo? Just because an idea offends you, don’t ever be afraid to question why it offends you.

Harari, Y. (2016). Sapiens. Harper Collins Publisher. New York, Ny.

Well done. For part 3, maybe something inspired by Gobekli-Tepe?

Ooh! I was unfamiliar with Gobekli-Tepe by name at first, but when I looked it up, I realized the book had talked about this as well. It is suggested by some to be the start of the Agricultural Revolution as this is what drew people together in large numbers, requiring, for the first time, large stores of food. Discussing this would totally be the next step in telling the history of humans 🙂

Jake, I would say that site is not so much about an ag. revolution, even if a strong case were made for it causing one . Rather, it is about an evolution of consciousness. Perhaps one speaking to the primacy of the spiritual in the history/nature of we Sapiens; i.e. Religion or something like it, did not arise in the first “cities” – it preceded them, perhaps provoked them into being. Then too, we might factor in, the appearance cave art, and of handprints on cave walls, throughout the world – in something like a Neolithic Axial Age… our forebears were saying something.

One hypothesis.

I appreciate your insight! With any kind of discussion on these topics, it’s hard to come to a firm empirical understanding because much of those times are lost to the flow of time. For example, the period known as the “Stone Age” is actually one marked by much more prolific use of wooden tools. However, over time, only the stone tools have remained to give us any perspective on the lives and minds of our earlier selves. So in understanding our forebearers, the best we can do is approximate, estimate, and reason out what would be most likely based on our current understanding of the world.