How to Save Society with Psychology

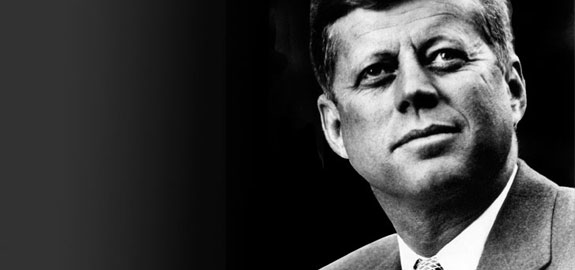

If destruction be our lot, we [will] ourselves be its author and finisher. – Abraham Lincoln from his speech “The Perpetuation of our Political Institutions” on his concerns regarding mob violence

Nowadays, it’s common knowledge that the U.S. — and countries around the world — face an increasing threat.

No, I’m not talking about the energy crisis. No, I don’t mean widespread displacement or homelessness. OK, not environmental problems either. What I’m really talking about (though, dang, we do have a lot to work on, don’t we?) is political polarization.

Underscoring what could be solutions to all of those problems I mentioned is the current dividedness between citizens. In fact, research shows that people believe their political views are growing more apart than ever before. And although such polarization makes it very difficult to enact policy solutions, there is yet another concern it presents. The potential for political violence.

Although survey data suggest that people are unlikely to individually engage in political violence, too much division can lead to seeing “the other side” as more than just one’s political rival…

So, today, let’s discuss what you can do to help reduce this threat of political polarization.

A STRAIGHTISH-FORWARD SOLUTION

Already, research has identified one of the best ways to reduce political polarization – and it’s something within all of our control. Have people with opposing views engage with one another.

For example, in one study, researchers wanted to test whether they could change people’s attitudes on a transgender bill in California. Although people tend to be very polarized on this topic, the researchers hired people to go door-to-door to simply engage with these people who held oppositional views.

Specifically, the researchers didn’t ask them to try to “persuade” the other person, only to have a dialogue where both sides expressed their opinions and lived experiences. As a result, the researchers actually found an increase in positivity toward the bill among those who had previously objected to it!

One of the reasons that simply engaging with people of opposing views is that people on “opposite sides” actually have more in common than they think. For example, nearly 90% of people – which includes both liberals and conservatives — support similar “common sense gun laws.” Or 85% of people – again including both liberals and conservatives – support access to abortion in at least some situations.

The issue is that when you don’t actually have these conversations, people generate incorrect assumptions about the other side. So, what are the assumptions that most prominently prevent people from having these discussions?

EXPLAINING THE LACK OF ENGAGEMENT

Now, although I generally cover other people’s research on this website, today’s topic is something I conducted research on myself. In fact, my colleague and I wanted to ask the very question we posed to you: why do people with opposing views resist engaging with one another?

To begin answering this, we recruited a sample of participants demographically representative of the US population. We then gave them a list of perceptions about people on the other side that might influence whether they engage with them (e.g., this other person will get emotionally agitated or be impossible to change).

What we found – scoring significantly higher than any other factor– was the perception of the other person’s ‘openness.’ In other words, even if the other person was extreme or very firm in their position, so long as you think this other person would “genuinely listen” to what you had to say, you would be open to engaging with them on the topic.

Because this factor had such a powerful effect on people’s willingness to engage with political rivals, we next wanted to know what predicts this perception. Here, we found that when you think a person’s opinion is based on emotions (vs. reason), you tend to automatically believe this other person will be ‘unopen’ on the topic. Or in other words, you don’t expect “to feel heard.” Unfortunately, this is a big problem for political polarization.

That is, people automatically assume “the other side’s” opinion is emotionally (vs. rationally) based, so people assume “the other side” will not genuinely listen to them on the topic. Because of these perceptions, both liberals and conservatives rarely engage with people who hold opposing views – even though both sides rate themselves as being open to hearing the other side’s opinion!

WHAT YOU CAN DO

The first step in overcoming any kind of misperception is to become aware of it. And in this case, I hope you’re able to recognize how you might make these misperceptions of those you disagree with.

As one way to help overcome them and promote engagement, try to think of all the rational reasons someone might hold the opposing opinion. Focusing on the reasons that underlie their opinion, can make them seem more open on the topic, encouraging you to speak with them.

Still, even with this awareness, it will take intentional effort (and patience!) on your part to have a productive discussion. However, we all need to try to engage with those we disagree with, before the divide between sides becomes too big for even civil discourse to bridge.

Openly,

Jake

Everyday Psychology: It’s important to note that these conversations with disagreeing others can be difficult to have. However, setting a few “ground rules” to any discussion can make them go easier. For example, try to let the other person speak first and genuinely listen as they express their opinion. The more you demonstrate openness toward them, the more likely they will be to show you more openness in return. Similarly, try to frame the whole conversation under a shared goal: you both want what is best for your country or society. Being aware that you both are simply trying to figure out the most accurate way to promote “goodness” in the world (rather than “be right”) can make people less defensive when it comes to hearing other opinions.

Broockman, D., & Kalla, J. (2016). Durably reducing transphobia: A field experiment on door-to-door canvassing. Science, 352(6282), 220-224.

Teeny, J. D., & Petty, R. E. (2022). Attributions of emotion and reduced attitude openness prevent people from engaging others with opposing views. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 102, 104373.