The Influence of Anchoring

The greatest deception men suffer is from their own opinions. – Leonardo da Vinci

Without any further information, if I asked you whether you would be more likely to buy a more expensive meal at a restaurant called Studio 97 or Studio 18, which would you say?

Clearly, the only difference between these restaurants (as far as you know) is the random number at the end of their names. Now, maybe one of those numbers is your lucky number which makes it easy (though which would also be weird; who likes 97 or 18?). But without knowing anything else about the restaurant, which do you think you’d be willing to spend more money at?

I’ll explain my mysterious intro in a moment.

First, let me tell you about an interesting study done back in the 70’s. Researchers gave participants five seconds to solve one of two math problems. That is, participants either saw:

1) 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 x 8

2) 8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1

When participants were asked to estimate the answer, those who saw the first problem gave a guess around 512. But those who saw the second problem gave a guess around 2,250. (The actual answer is 40,320—which really just comments on how bad most people are at big math.)

But even more interesting is the discrepancy in response when both problems are exactly the same numbers?

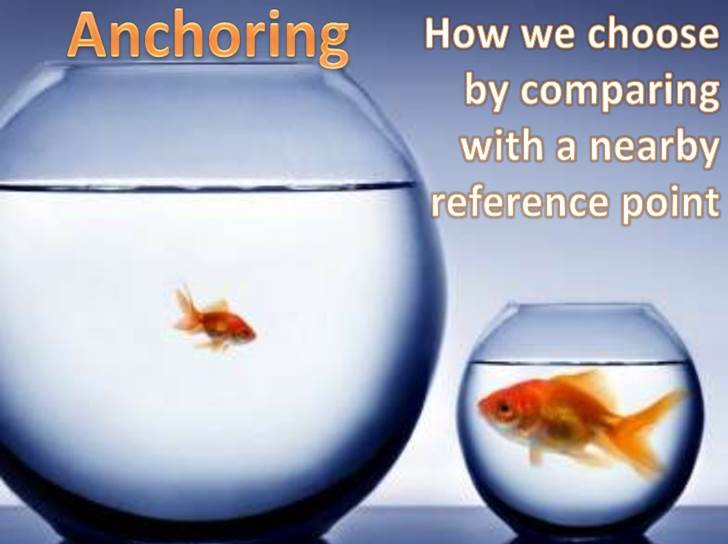

This is what’s known as anchoring.

For example, when we see the first problem, our brain automatically thinks of a smaller answer (because 1 is first) whereas when we the second problem, our brain automatically thinks of a larger number (because 8 is first).

Using this initial, automatic estimation, our brains then try to come up with a more accurate estimate by “anchoring” (or using the information from our first, intuitive calculation) to come up with a second more probable answer.

Let me give another example that may make this clearer.

Researchers asked participants to estimate how old Gandhi was when he died in a two-step process. First, they either asked the participant: “Was Gandhi older or younger than A) twenty-nine years, or B) one hundred and nine years when he died?” Clearly, if you’re participant A you say older, and if you’re participant B you say younger.

Subsequently, researchers asked participants to give them their estimates for Gandhi’s age when he died.

For participant A, the guess was about 66.7, but for participant B the guess was about 99.6!

That’s over a 30 year difference simply because the participants “anchored” on that initial question with the absurd age.

Think of when you’re with friends and you’re trying to guess how much something may cost. Have you ever come up with a pretty big number only to hear your friend first say something smaller? All of a sudden you think, “Well, maybe my guess should be a little lower…”

Returning to my initial example, the researchers found that participants were willing to pay a significantly larger amount at the restaurant called Studio 97 (vs. Studio 18). That is, because seeing the bigger number in the title of the restaurant, made people anchor on a larger number for estimating how much they’d spend!

The next time I email my Dad for some funds, I think I’ll make the subject line read: 1,000,000 reasons why I love you…

Anchoredly,

jdt