Psychology Crisis? Not Yet

The characteristic of scientific progress is our knowing that we did not know. – Gaston Bachelard

If you’ve seen any news headlines about science lately, you’ve probably read something like: “Out of 100 psychological studies, over 70% failed to replicate!” (sometimes, they even use two exclamation points)

Recently, there was an international collaboration by psychologists to take well-known studies and try to “replicate” them, i.e., through rerunning a study, turn up the same results as the old one. However, from this “Reproducibility Project,” only a few effects actually achieved this (according to the researchers’ criteria).

So is psychology in a crisis? Should we distrust all the findings from the past 100 years? After getting my degree, will I just have to move back in with my parents?

The answer to all of those is “no” (eh, maybe not the last one).

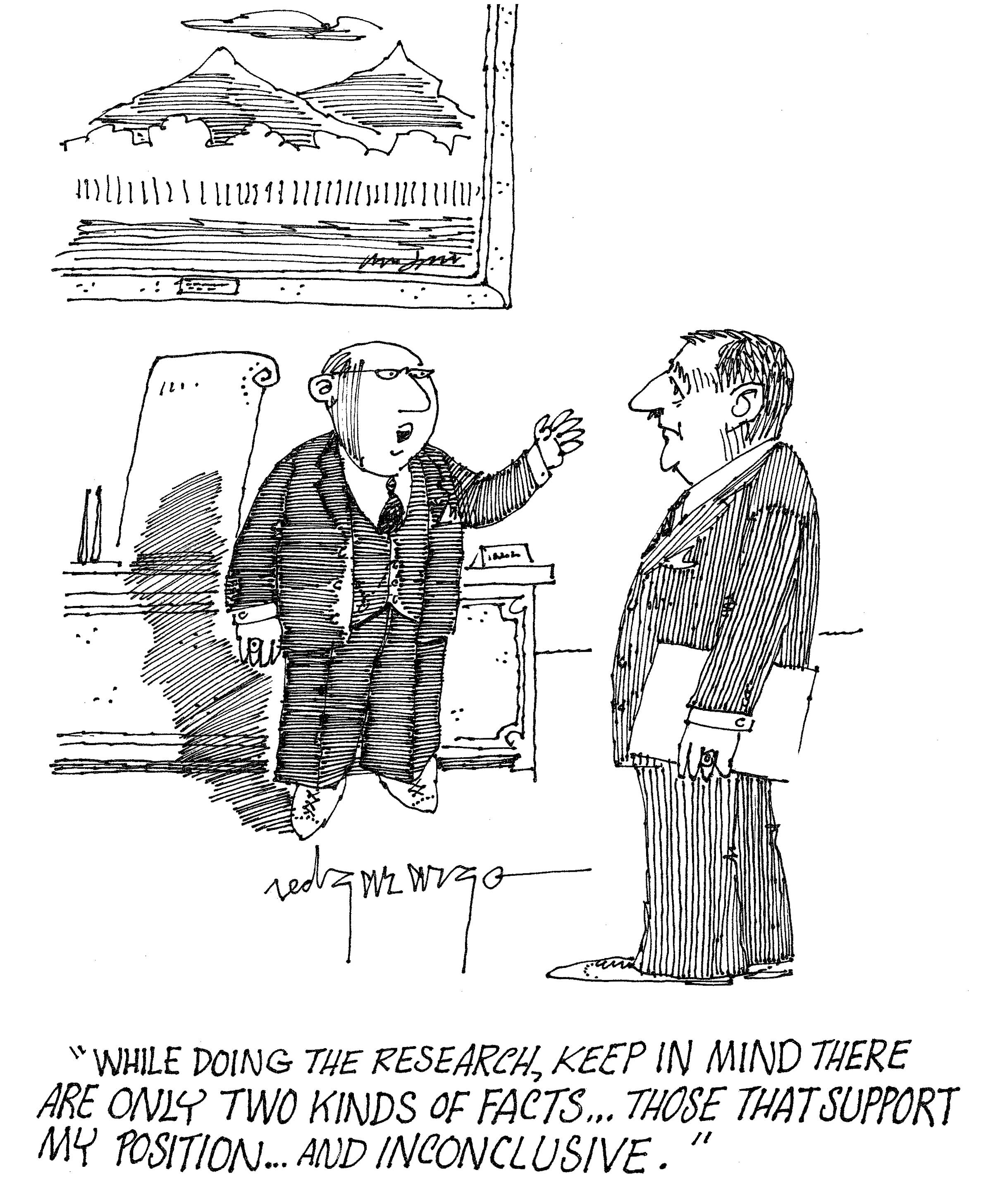

Lisa Feldman-Barrett (one of my favorite social psychologists) comments on this report by saying: “Science is not a body of facts that emerge, like an orderly string of light bulbs, to illuminate a linear path to universal truth.”

That is, science is not just one study—BOOM—and you have truth. It is an accumulation of studies over time. It is a development, a process, an evolution of understanding. The failure of studies to replicate doesn’t mean the prior ones were necessarily false; it likely means that there was something significantly different between the first study that found the effect and the second that didn’t.

Unlike the disciplines of physics or chemistry, which work with inert objects in vacuum-sealed environments (though, their studies, too, face similar repliciability issues), humans are incredibly complex organisms who can respond incredibly differently based on the subtlest shift in contexts.

For example, let’s say you’re looking at a variable called Need for Cognition (NC; i.e., the personality preference to engage in deep thinking or complex problem solving).

Now let’s say you want to predict that high NC people will be less persuaded by irrelevant cues in an advertisement (e.g., a celebrity endorsement) than low NC people. That is, those who like to think deeply about things will realize that a celebrity’s endorsement really doesn’t tell you about the merits of the product, whereas low NC people will simply see: “LeBron James uses this shampoo? It must be good.”

So the researchers run this experiment and their hypothesis is supported: high NC people were less persuaded by celebrity endorsement.

Now let’s say 5 years from now (as is the average difference in time between the original studies and the ones replicated in this project), scientists want to reproduce that NC finding, so they run a near carbon copy of the original study on new participants. But alas, now it looks like high NC people are just as persuaded as low NC people!

Should we entirely discredit the effect?

I think you know my answer to this.

For example, what if the first study was run on a Tuesday (when high NC people are in a high-thinking mode), but the second study was run on a Saturday (when no one likes to think much). That would probably result in a failed replication.

What if LeBron James—the celebrity endorser in the first study, used again in the second one—isn’t as famous anymore? That will also affect the replicability.

In essence, there is no such thing as a perfect replication; there will always be differences between studies and it is the researchers’ job to figure out what those differences between studies are and how those differences could be producing different results.

Again, science is a body of knowledge, not just a single limb. Rather than construing the failed replication as evidence the effect doesn’t exist, we should see how it helps delineate the boundary conditions for when we get the effect (i.e., what are the other variables that “turn off” or “on” the effect). And as we know more and more about these boundary conditions (e.g., only on days when people want to think do we get the effect), then we have a more complete understanding of psychology.

Now, I’m not here to say these replicability findings are meaningless, but I will point out that psychology is one of the youngest sciences in practice, centuries younger than almost every other. And still, we have used it to do things like improving environmental care, increasing organ donation, discovering best practices for rehabilitation, and countless other things.

So to think that a few failed replications means a crisis for psychology is the wrong attitude to take. Rather, we should think about how this study speaks to people’s misconceptions about science in general, and how the media needs to step up to the challenge of reporting a more accurate depiction of how science actually functions.

Replicably,

jdt

Well said Doctor teeny!!! Congrats

Thank you, Patty! But I’m not a doctor yet 🙂 Give me 3-4 more years