Stereotype Threat

One’s reputation, whether false or true, cannot be hammered, hammered, hammered into one’s head without doing something to one’s character. – Gordon Allport

After receiving a number of messages about the last two posts I’d written on self-affirmation, I was surprised to find that I had never discussed one of the primary uses for it: combatting stereotype threat.

As one of our readers shared last week, being one of the few women of color on campus (or really, anywhere) can be difficult as one’s racial and gender uniqueness are constantly salient to oneself. That is, the more you are a minority in a situation (whether that is your race, your political views, etc.), the more that aspect of your identity is present in your mind.

DISTINCTIVENESS AND SALIENCE

In fact, when researchers looked at 1st, 3rd, 7th, and 11th graders, they found the same finding for ethnicity in the classroom. That is, about 1% of white students (who made up the vast majority of students) listed their ethnicity as part of their self-concept, whereas nearly a third of minority students listed theirs.

And while it is good to identify with your gender and race, there are some problems that can arise with it depending on the situation.

THE AWFUL POWER OF STEREOTYPES

Regardless of whether you express or endorse certain stereotypes, you are nonetheless aware of them. For example, I could pretty much list any minority and you’d be able to come up with a common stereotype about them. And again, even if you abhor those stereotypes, simply being aware of them can still impact your attitudes and behavior—doubly so if that particular stereotype applies to your gender or racial identity.

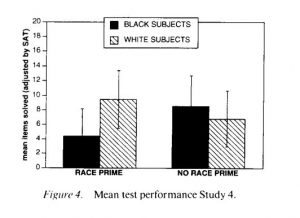

In the first study to document this, Claude Steele (an OSU alum!) brought white and black Stanford students into the lab to take a very challenging verbal test (from the SAT). Although everyone in the study answered the exact same 20 questions, there was a subtle manipulation between conditions:

For half of the participants, they simply took the test, while the other half took the same test, but they answered some standard demographic questions beforehand (like age, year in school, and race).

Now, when students took the test without that racial identifying question at the beginning (the right bars in the graph), both black and white Stanford students performed equally well. However, when the black students filled out that demographic information beforehand (which makes their race salient, i.e., a “race prime”), they performed significantly worse than the white students.

WHOA…WHY DOES THIS HAPPEN?

Stereotype threat is a robust one, not only shown with African Americans in academic settings, but also with women on math tests (where they’re stereotyped to be worse than men), homosexual men in childcare (where they’re stereotyped to be “dangerous” to children), and in fact, it’s even been shown with white male “mathletes” who were reminded of how Asians tend to excel in math (where, compared to white men who didn’t get this reminder, they performed significantly worse).

Researchers contend that when a stereotype about oneself is activated, it occupies one’s working memory, which takes up mental resources that could be applied to the task at hand. For example, when black students are reminded of their race before taking a test, their minds become occupied with the concern that their performance will confirm the stereotype of unintelligence that others have/are aware of about them.

Much work has been done to try to reduce the effects of stereotype threat, but being aware of it is the first step. And with concerted effort, scientists and policy makers can work together to reduce stereotype threat wherever it systematically exists. Indeed, because of Dr. Steele’s seminal work and others’ dogged persistence, the SAT actually moved the demographics questions to the end of test.

Stereotypically,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: Can you think of a time when your performance on something suffered because you were concerned with a particular stereotype about your race, gender, political views, etc.? Or regardless of stereotypes, have you ever been the sole representative of a group and felt like everyone’s eyes were on you as a result of that? Such awareness can lead to impaired performances as well.

McGuire, W. J., McGuire, C. V., Child, P., & Fujioka, T. (1978). Salience of ethnicity in the spontaneous self-concept as a function of one’s ethnic distinctiveness in the social environment. Journal of personality and social psychology, 36(5), 511.

McGuire, W. J., McGuire, C. V., & Winton, W. (1979). Effects of household sex composition on the salience of one’s gender in the spontaneous self-concept. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 15(1), 77-90.

Schmader, T., & Johns, M. (2003). Converging evidence that stereotype threat reduces working memory capacity. Journal of personality and social psychology, 85(3), 440.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of personality and social psychology, 69(5), 797.

One Comment

Comments are closed.