Easy vs. Difficult, You Decide

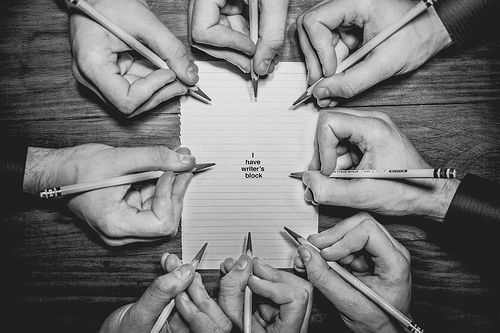

What is written without effort is in general read without pleasure. – Samuel Johnson

Let’s imagine you had the goal “make more money.” Which of the following options would you prefer:

(1) A long and effortful path to making more money? or (2) A quick and easy path to the same outcome?

If you at all resemble the decades of research done on this and related questions, there’s a simple answer:

Easier = better.

But why is effort such a negative thing? And when is it actually desired?

BOTH EASIER AND HARDER THAN IT LOOKS

As a simple example, if the exact same advertisement is printed in easy-to-read (vs. difficult-to-read) font, people report liking its advertised product more.

At our evolutionary core, we are designed to conserve energy so that we have it when we need it (e.g., to escape a predator; catch a prey; etc.). Although our energy is directed toward other “survival” tasks these days (e.g., staying awake at work), most people’s biology nonetheless makes high effort tasks feel unpleasant and low effort tasks feel good.

Moreover, the things most familiar and relevant to us are easy (vs. difficult) to do and process. Thus, even when we’re “tricked” into perceiving something was easier (e.g., an easier-to-read advertisement), we tend to evaluate it more positively because we naturally associate those “feelings of ease” with familiarity and personal relevance.

Yet, even though extensive research shows that we prefer low (vs. high) effort stimuli, can you think of times where difficulty is actually a good thing? If not, some clever have done it for you.

ACHIEVING ONE’S GOALS ARE HARD!

In the real world, achieving something of real value usually requires a fair deal of effort–it’s not easy to attain our prized goals! Thus, when it’s easy (vs. difficult) to achieve these outcomes, low effort can actually result in more negative evaluations.

For example, researchers activated the goal to “be kinder” for some participants, while others received no goal manipulation. The researchers then gave participants an advertisement for a charity that was either easy or difficult to read (see the figure to the side).

Afterward, the researchers measured how much money participants actually donated.

For those who didn’t have a goal active, they donated more for the easy-to-read ($0.53) versus the difficult-to-read appeal ($0.26).

In contrast, those who had the “be kinder” goal active actually donated less after the easy-to-read ad ($0.30) compared to the difficult-to-read one ($0.70)!

So, what’s up?

EFFORTFUL QUALIFICATIONS

First, it depends on how you’re evaluating your route to goal pursuit. That is, if you’re evaluating how this route to your goal makes you feel, high effort will lead to negative evaluations. However, if you’re evaluating how this route to your goal compares to other possible routes, high effort leads to positive evaluations.

Here, when comparing possible routes to one’s goals, high (vs. low) effort tends to signal “this is a route worth pursuing!” But, if you’re simply focused on how this route to your goal makes you feel, that high effort is unpleasant, which leads to negative evaluations.

The second important qualification of high effort having a positive effect is that you need to attribute that effort to your pursuit of the goal itself. For example, if you recognize that the extra effort you’re putting in is due to unrelated factors—like the readability of the text—you will realize your effort has nothing to do with your goal pursuit.

So, if I personally had the goal to make more money, how would I evaluate the effort I put into writing this blog? Well, let’s just say it’s a good thing that the goal of this website is not to make me more money.

Effortfully,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: What are some other aspects of your life where high effort could lead to some of these positive outcomes? From the research I covered today, there were a few other interesting studies I didn’t discuss. For example, when the researchers made it more (vs. less) difficult to evaluate the picture of a woman, they rated her as more attractive. Or when consumers thought it would be harder (vs. easier) to secure a bottle of wine, they thought it tasted better. Of course, the same qualifications I outlined above apply here, too: these results depended on whether people attributed that effort to how they were feeling vs. how this task influenced their goal, and whether the effort was due to their goal pursuit or another unrelated factor.

Kim, S., & Labroo, A. A. (2011). From inherent value to incentive value: When and why pointless effort enhances consumer preference. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(4), 712-742.

Labroo, A. A., & Kim, S. (2009). The “instrumentality” heuristic: Why metacognitive difficulty is desirable during goal pursuit. Psychological Science, 20(1), 127-134.

Zipf, G. K. (1949). Human behavior and the principle of least effort. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley