Implicit Bias

The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend. — Robertson Davies

If you’ve listened to the news recently, you’ve probably heard the term “implicit bias” used in regards to prejudice. It has come up in the media quite a bit with the recent police shootings of black men, and it’s important to understand what implicit bias really means.

Now, in regards to race, explicit bias refers to the conscious recognition that one’s race is superior to another’s. Although people may not express their explicit bias, so long as they endorse these stereotypes or negative expectations for another race, they are demonstrating explicit bias.

Implicit bias, on the other hand, is not so overt and results from subtle cognitive processes that operate below our conscious awareness.

For example, imagine you’re sitting in your car at night, waiting for a friend. Although you’re not really thinking about it, all of a sudden, you decide to lock your car. However, only upon reflection do you realize you did this only after seeing a black man walk by.

Now, consider a report of a black man being shot by a police officer. Unfortunately, the details are a little ambiguous with contradictory eyewitnesses. Without even realizing it, though, one’s stereotype of “black people are aggressive” may strengthen their confidence in one witness’s report, while undermining another.

Implicit bias, then, isn’t the same impassioned hate speech of the KKK; however, it is still an underlying bias against a certain race. But if it occurs beneath our conscious awareness, how do we even know if we have it?

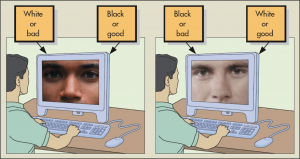

There are multiple ways that researchers can test for implicit bias, but the most common method is called the Implicit Association Test (IAT). In it, participants sit at a computer and are shown pictures of black or white faces, which they are told to categorize—as fast as they can—as ‘black’ with one keystroke or ‘white’ with another.

Then, after participants have become familiar with this task, the objective alters. Now, participants are shown a bunch of positive words (e.g., cake) or negative words (e.g., cockroach) and asked to categorize them with one keystroke for ‘good’ or another for ‘bad.’

And after this, comes the test of implicit bias.

In the third step of the procedure, any of the previous objects (white faces, black faces, good words, or bad words) may appear on the screen. But instead of a keystrokes only categorizing one type of object, it categorizes two. For example, in one case, the participants will press a single key if the object on the screen is a good word or a white face, while the other key is to be pressed if the object is a bad word or a black face.

Typically, people are very fast at categorizing words and faces when they’re paired like this; however, if ‘black’ and ‘good’ are mapped onto the same key, people tend to be much slower. That is, the lesser the extent that you associate black faces with good things, the slower you’re going to be able to categorize them under the same label.

Amazingly, in research done in 2006, by the time children have entered kindergarten, they are already showing this implicit pro-white bias. Moreover, they are also demonstrating explicit bias: 86% of the children, when shown a picture of a white or black child to play with, choose the white child.

But whereas this explicit bias decreases over time (only 68% of 10-year olds prefer the white child, and by adulthood, that number drops close to 50%), one’s implicit bias remains constant, with adults showing it just as much as the kindergartners.

And although you may think that something as minor as this “implicit bias” has no effect, we’ll discuss next week where such a perception is mistaken.

Explicitly,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: Want to know the extent of your own implicit bias? You can follow this link to take the test for yourself.

Baron, A. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2006). The development of implicit attitudes evidence of race evaluations from ages 6 and 10 and adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(1), 53-58.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.