Questioning Our Beliefs

The human understanding when it has once adopted an opinion draws all things else to support and agree with it. — Sir Francis Bacon

If humans could answer one question to solve the world’s problems, it would be this: How do you persuade someone to believe something other than what they do?

Or so begins my free course on the psychology of persuasion.

But I stand by that claim: if we could convince political parties to compromise or feuding nations to work out peace, the world would be a much better place. And although we know a lot about the psychology of persuasion (you remember my free course, right?) we know very little about how to persuade people with extreme attitudes.

Let me give you an example.

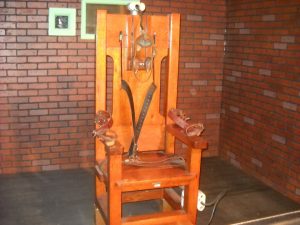

In one of my favorite studies, researchers looked at changing participants’ attitudes toward capital punishment, a complex yet often  very polarized social issue. With a mix of both strongly pro- and anti-capital punishment participants, the researchers then gave them two “scientific studies” on the effectiveness of the death penalty.

very polarized social issue. With a mix of both strongly pro- and anti-capital punishment participants, the researchers then gave them two “scientific studies” on the effectiveness of the death penalty.

Now, in reality, the results of the two studies were completely fictionalized by the researchers; however, the methods and procedures described in them did come from actual scientific practices. Importantly, though, in one of the scientific “reports,” capital punishment was proven effective, while in the other “report,” it was not.

Simply, then, the participants were asked to evaluate the quality of research and decide which article was more convincing.

And guess what? The pro-capital punishment participants favored the study that demonstrated its effectiveness, while the anti-capital punishment people found the other, contradicting study more valid.

And even worse: both groups became more extreme in their stances after reading the information.

Because the world is so gray (even the interpretations of some scientific evidence), we typically process information in line with our previously held beliefs. And if those beliefs are extreme, the more likely we are to make up an excuse, justify, or interpret counter-evidence in whatever way best fits our established picture for the world.

Well, if people with extreme attitudes even entertain counter-arguments in the first place.

During the 2004 presidential election, researchers put “committed democrats and republicans” in a brain scanner (an fMRI) and presented them with unflattering information about their preferred candidate. And the brain scans revealed something startling: participants didn’t engage the sections of their brain involved with “cold reasoning” or emotional control.

In other words, when people with extreme attitudes are confronted with contradictory information, they don’t cognitively process it to the same extent they would for other, less “threatening” information.

Researchers at three Israeli universities set out to see if they could convince Israeli participants to change their stance on the Israeli-Palestine conflict (i.e., to become less pro-Israel). But to do it, the researchers gave these participants extremely pro-Israel arguments.

In what’s been coined “paradoxical persuasion,” you essentially provide someone with arguments that support their current stance but take it to an even more extreme place than they’re willing to go.

For example, if you were trying to convince someone to become less opposed to capital punishment, you could make the argument: “You know what, there should be a maximum limit of 10 years for all crimes—no matter what they are—let alone ban capital punishment.” The researchers speculate that such extreme arguments force you to consider the underlying bases for your belief, which can sometimes lead to readjusting your stance.

And with this logic in the Israel-Palestine study, the researchers actually found that using this technique moderated the extreme stances.

So how can we use this information to make the world a better place? Well, the first step is educating people about the blinding power of extreme attitudes, and what better way to do that than sharing this blog?

Not As Extremely,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: When considering how your own personal beliefs may be influencing your interpretation of the world, just consider climate change. Do you find the scientific evidence supporting the existence of climate change more valid? Or do you find the work opposing it to be more convincing? And more importantly–why? If you ask NASA, though, they side with the 97% of scientific studies documenting the existence of climate change.

Hameiri, B., Porat, R., Bar-Tal, D., Bieler, A., & Halperin, E. (2014). Paradoxical thinking as a new avenue of intervention to promote peace. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(30), 10996-11001.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of personality and social psychology, 37(11), 2098.

Westen, D., Blagov, P. S., Harenski, K., Kilts, C., & Hamann, S. (2006). Neural bases of motivated reasoning: An fMRI study of emotional constraints on partisan political judgment in the 2004 US presidential election. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 18(11), 1947-1958.

One Comment

Comments are closed.