The Robbers Cave Experiment

Peace is not an absence of conflict, it is the ability to handle conflict by peaceful means. — Ronald Reagan

Lately, it’s felt like groups are more and more in conflict with each other. Republicans versus Democrats. Nation One versus Nation Two. Ninjas versus Pirates. (Obviously Team Ninja over here.) And in understanding these tensions–and solutions to them–there is an illustrative story I will share.

The story of one of social psychology’s most infamous experiments.

STAGE ONE: TWENTY-TWO YOUNG BOYS

In the summer of 1954, an increasingly well-known social psychologist, Muzafer Sherif, randomly selected twenty-two well-adjusted boys about 12 years old and from similar, middle-class backgrounds. They were all in the same year at school but had never interacted with one another before. The plan, then, was to have them participate in a very unique summer camp…

Before arriving at the 200-acre camp in Robbers Cave State Park in Oklahoma, the boys were randomly divided into two groups and brought to the camp in separate buses and housed in cabins on opposing ends.

Once these identities began to form, the researchers let slip that there was another group of boys on the same campgrounds. And almost immediately, an interesting change overtook the groups. For example, without any prompting, each group began insistently asking the researchers to let them engage in competitions with the other group. Moreover, each group began to become very protective of their facilities, even complaining that the other group might abuse them.

Then, with tensions on the rise, the researchers introduced some actual friction…

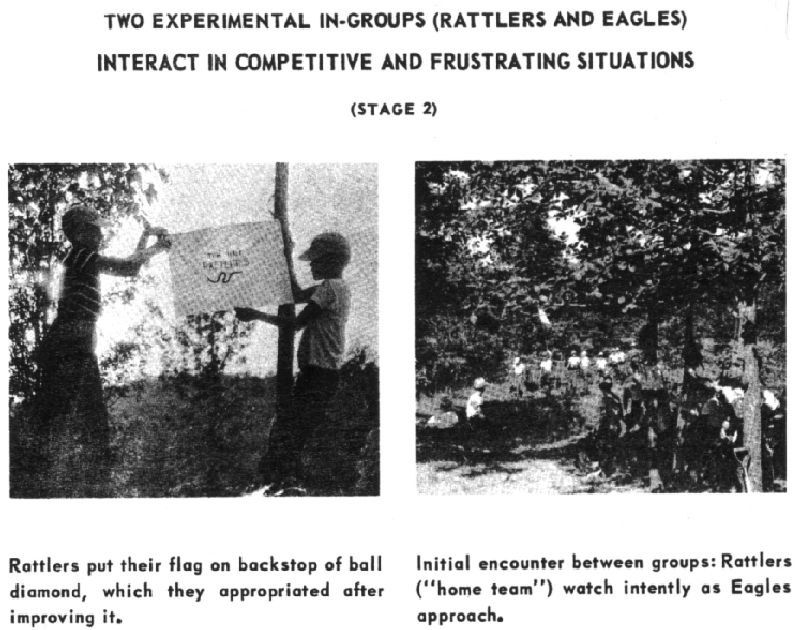

STAGE TWO: TROUBLE BREWS

Without actually initiating any competitions, the counselors expressed that they would have some competitive activities between the groups. And importantly, the winning side would receive medals, trophies, and prizes.

Upon learning this, a fire began to burn in those little boy hearts.

And when the two groups were actually brought together for the first time in the cafeteria, “there was considerable name-calling, razzing back and forth, and singing derogatory songs by each group in turn” (Sherif, 1961). Soon, there was talk within each groups of burning the opposing group’s flag. And after The Eagles defeated The Rattlers in a series of competitions (through the discreet aid of the researchers), The Rattlers organized a raid on The Eagles, stealing any medals and toys they could get their hands on.

In fact, the two groups nearly came to blows were it not for the researchers’ intervention as the previous name-calling of “braggers” and “stinkers” turned to much more offensive remarks. In short, the conflict between groups had become very, very real…

STAGE THREE: PACIFYING TENSIONS

At first, the researchers tried a number of “get-to-know-you” activities, such as sharing a meal, a movie, and even fireworks for the Fourth of July. However, these attempts only provoked the boys further, many of the events ending in more name-calling or even food fights.

At which point, the researchers tested out their primary hypothesis: activating a superordinate (i.e., higher-order) goal can bring conflicting groups together. That is, the researchers crafted problems that required solutions beyond the resources either one group could provide.

For example, the researchers convinced the boys that all the drinking water for the camp had been blocked because of “vandals” in the area. Bringing both groups to the pipe proving to be the root of the issue, the boys had to work together to figure out how to get water for everyone.

And amazingly, as antagonistic as the groups has become, by the end of the camp, they wanted to take the same bus back; they wanted to sit across party lines; and when they stopped at a refreshment stand, The Rattlers—who had been awarded $5 for winning one of the earlier activities—volunteered to use that money to buy malted milks for all the boys.

STAGE NEXT: APPLYING IT TO OUR OWN LIVES

This famous study illustrates (and led to the development of) realistic conflict theory. This theory specifies that when there are limited resources—be that food and drink, jobs, political clout, reputation—conflict will naturally breed between groups.

Importantly, though, these resources don’t even need to actually be limited; they could simply be perceived as limited. For example, even if immigrants aren’t depriving native born workers from job opportunities, the mere perception that they could be can lead to conflict and prejudice against them.

So, when thinking about our own world, one way to reduce these conflicts is to categorize ourselves in more encompassing groups, rather than ones in competition. For example, rather than thinking about us as Democrats versus Republicans, we should think of ourselves all as Americans in pursuit of shared, superordinate goals (e.g., the opportunity for happiness for all).

Thus, the next time you feel some negativity toward another group, try to focus on the bigger picture and don’t be outclassed by some 12-year-old boys 😉

A-28-year-old-boy,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: In addition to trying to activate shared goals and common group identity, another prominent theory for reducing tensions between groups come from Gordon Allport’s famous contact hypothesis. Here, research shows that meaningful interactions between groups leads to reduced group antagonism. For example, if Democrats and Republicans got together to spend meaningful time together (e.g., doing activities they both enjoy, working together on a problem, etc.), it would help reduce some of the prejudice they hold for one another. Importantly, though, not all intergroup contact results in better outcomes. For example, if people are in the same area (e.g., a subway car) but don’t actually have substantial interactions with another, this kind of contact can actually backfire, making people have even more prejudice toward the outgroup member.

Sherif, M. (1961). Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The Robbers Cave experiment (Vol. 10, pp. 150-198). Norman, OK: University Book Exchange.

Pondering the possible results of this scenario among other groups, I wonder if people can see beyond their differences to Desire to cooperate, even for a common goal.

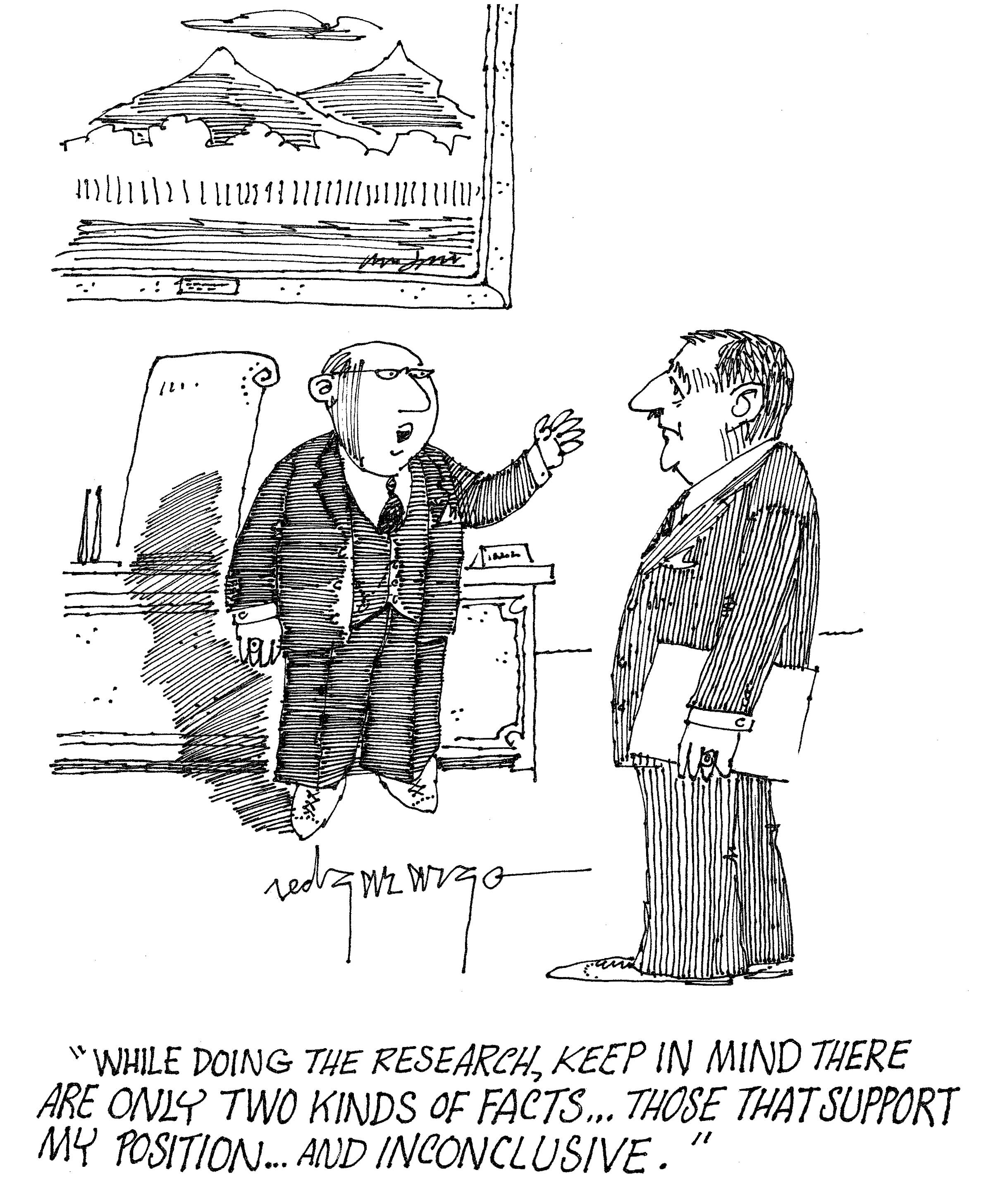

Great question! Psychologically speaking, we would suspect that other groups operate off of similar principles to the ones I described above; however, they may be stronger or weaker depending on the cohesiveness of the group. Nonetheless, getting people to share a common goal (or even a common enemy) can be enough to unite even the most conflicting groups.