Mirror, Mirror, Am I Really This Good Looking?

Illusion is the first of all pleasures. — Oscar Wilde.

So I don’t know about you, but I put on about 27 pounds after Thanksgiving. And no, we’re not talking muscle here. That’s about 3 pounds of Turkey, 24 pounds of stuffing, and pie.

It’s for everyone best interest if I leave out the amount of pie I consumed.

But looking in the mirror that Friday after Thanksgiving, or rather, trying to fit into my socks (I keep all my weight in my ankles) I didn’t feel as attractive as I usually do while staring at my reflection. Which means I placed myself 3rd on Maxim’s list of hottest guys instead of second.

Come one, we all know Johnny Depp is just way too dreamy.

Now we all have our own perceptions of what we look like, but aside from this Thanksgiving fattening, how do people tend to view themselves?

A remarkably clever study was done by Epley & Whitchurch (2008), where they invited participants into their study to have their picture taken. After getting the photo, participants filled out a few questionnaires and then left with instructions to come back a few weeks later.

And in those weeks between was when the cleverness happened.

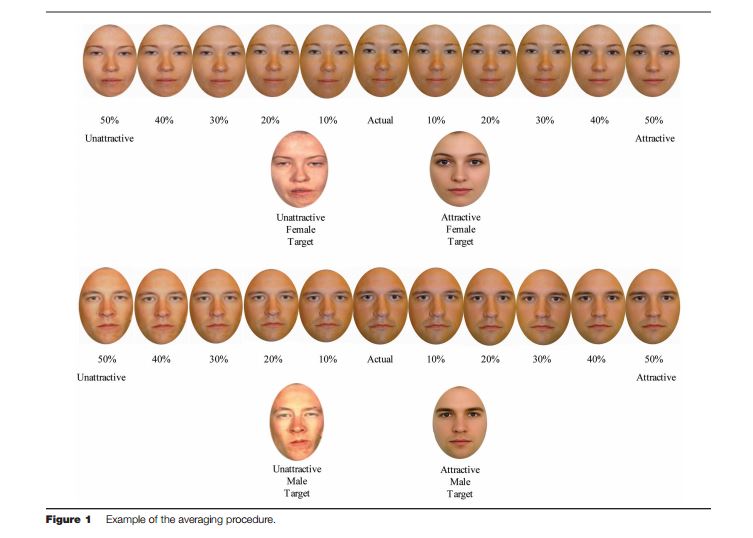

If you see the picture on the right, researchers took that original photo of the participant (the one labeled “actual” in those strings of pictures) and blended it with either an attractive or unattractive face (the attractive face is a “composite” of a bunch of faces, or in other words, an averaging of features, whereas the unattractive face comes from individuals with a facial abnormality).

When participants arrived at that second date, the researchers gave them the 11 pictures of themselves and told them to select the one picture that was actually real. So, how accurate were participants?

About 65% of them selected faces that were at least 10% more attractive than their actual photo. In fact, in a follow-up study, about 35% of participants believed the real picture of themselves was one that had been digitalized to be 30-40% more attractive.

In a subsequent study, the researchers also had participants do a similar task with a close friend as well as a stranger. That is, researchers morphed a picture of the participant’s friend or the experimenter who ran their study and had participants once more try to select the real photo.

When it came to the stranger, participants were very accurate in selecting the actual photo; however, when trying to pick out the real photo of a friend, this enhancement-bias once again emerged: people tended to select a version of their friend that was at least 10% more attractive.

As I’ll discuss in forthcoming weeks (though I’m not promising next week), I’ll talk more about our natural, delusional views of ourselves. But for now, just know:

Scientifically speaking, no one’s as attractive as they think they are.

Attractively,

jdt

Epley, N., & Whitchurch, E. (2008). Mirror, mirror on the wall: Enhancement in self-recognition. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(9), 1159-1170.

One Comment

Comments are closed.