Psychology of Food

There is no sincerer love than the love of food. — George Bernard Shaw

Since the prior week, something miraculous has happened: there’s food in my refrigerator. As a graduate student, my shopping cart often consists of ramen, peanut butter, and a six-pack of PBR. But as of last Saturday, I have vegetables and hamburgers, sandwich supplies and pasta makings, yogurt, granola, granola bars, even an apple pie!

So how did this happen?!?

She’s a deity that goes by the mortal name of Rochelle Teeny. Yep, my mom came to Columbus and spent the week with me, pampering me more than any son should ever be pampered. (But it was great.)

Nonetheless, all this food got me thinking (well, what doesn’t get me thinking?) that I think I’m a little hungry for some food psychology…

UM, SHOULD I EAT THAT?

UM, SHOULD I EAT THAT?

Before this last week, I would constantly be playing a game of Russian Roulette with expired food. Any hair on it? I think we’re good.

When it comes to buying food, though, consumers rate “food freshness” as one of the most important factors in their purchasing decision (just below taste and nutrition and equal to price and convenience). In fact, if an American learns they have purchased an item past its expiration date, only 7% report they would actually consume it.

But now let me pose to you a hypothetical:

Let’s say you’re hungry when you’re looking through your fridge and you see some yogurt a couple days past its expiration date. Would you eat it? Maybe? Yes?

What about in this situation: Say, you’re hungry and going through a friend’s fridge when you find his expired yogurt. How do you feel about eating that one now?

Research shows that people are significantly more likely to eat expired food when they own it, because they tend to approach their own food with questions like, “This looks good, right?” whereas when it’s others’ food, we approach it with statements like, “I don’t know about that…”

In other words, the way we frame our “hypotheses” (i.e., our guesses at whether the yogurt is edible) can really influence our behaviors–the more favorable the opening hypothesis, the more favorable the overall evaluation.

HOW A FOOD’S PACKAGED

In some states, they have been requiring restaurants to put the calorie amounts next to all of their food. But really what matters for influencing dining choices is all in the name.

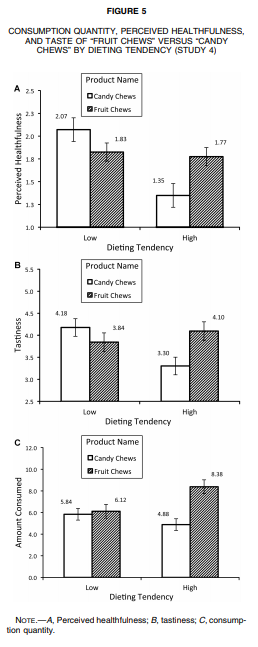

Researchers gave participants a cup full of jelly beans and either told participants they were called “candy chews” or “fruit chews.” The researchers then wanted to know how these mere names may influence people’s perceptions of the candy’s healthiness.

Interestingly, for people who aren’t on a diet, they rated the healthiness of each candy at similar levels, (see the top graph on the right, the two bars on the left side). But for high dieters (the two bars to the right), they rated the candy chews to be significantly unhealthier than the fruit chews. Ironically as a result, however, those people on a diet actually ate the most jelly beans when watching a movie—but only when they were named the “healthier” fruit chews (see bottom graph, far right bar).

As a final way that seemingly tangential factors can influence your food consumption, look no further than the packaging itself.

In fact, researchers (one of whom is at OSU!) found that using clear (vs. opaque) bags could influence how much people ate from them.

Transparent bags allow you to see all the fun, small food in there (making them salient and more likely to be consumed); but transparency also means you can monitor how much you eat—which prevents us from taking too much of the big stuff. For opaque bags, big foods are eaten more because you can’t as easily monitor how much you’re eating, while it impairs small and colorful food eating because they’re not as salient.

I’M JUST HUNGRY

Well, it’s very late here in Columbus when I’m finally getting this post up, and that last heading came straight from the vocal cords of my belly. So, good night or good morning to all! 🙂

Sleepily,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: Although I touched on it in the discussion of the expired food study, this notion of biased hypothesis testing is a robust phenomenon in people. That is, the way we ask a questions can really influence our subsequent attitudes and behaviors toward it. For example, if you like a particular political candidate, but there are whispers of him or her doing something scandalous, what are the questions you would use to figure out the truth? What pieces of evidence would you count as evidence? How would this differ if it was a candidate you disliked? The process we take to answer a question can often tell us the answer to our question by the virtue of the process itself.

Deng, X., & Srinivasan, R. (2013). When do transparent packages increase (or decrease) food consumption?. Journal of Marketing, 77(4), 104-117.

Irmak, C., Vallen, B., & Robinson, S. R. (2011). The impact of product name on dieters’ and nondieters’ food evaluations and consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(2), 390-405.

Sen, S., & Block, L. G. (2008). “Why my mother never threw anything out”: the effect of product freshness on consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(1), 47-55.