Arousal

The energy of the mind is the essence of life. — Aristotle

I’m going to describe a psychological state, and then let’s see if you can guess the type of situation that caused it:

I’m going to describe a psychological state, and then let’s see if you can guess the type of situation that caused it:

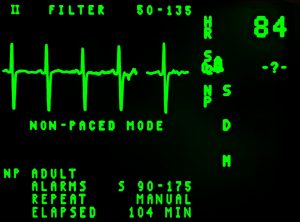

Your heart is beating faster than usual, and you’re taking bigger, even faster breaths. If asked, you’d say you feel very awake.

Can you think of a kind of situation that would evoke these feelings?

Maybe you imagined having to give a big speech, or maybe you just won an award, or maybe you downed a large coffee with an extra shot of espresso.

Regardless, these bodily reactions (increased heartrate, greater breathing, feelings of alertness) are all signs of the fundamental psychological state of physiological arousal: the activation of one’s sympathetic nervous system and the mobilization it provides.

But arousal is not as straightforward as you may think, and below, I discuss two important features of it that everyone should know.

POSITIVE OR NEGATIVE AROUSAL?

In 1962, two researchers by the names of Stanley Schacter and Jerome Singer ran a now classic experiment. Back when scientists received less oversight, the two researchers injected participants with ½ cubic centimeter of epinephrine, essentially, adrenaline.

Before the injection, participants believed the drug was a “vitamin supplement” which should only impact their vision. In truth, the researchers wanted to know how people would evaluate unexpected feelings of arousal, and crucially, whether their environment could influence that interpretation.

To test this, physiologically aroused participants interacted with a confederate (i.e., a member of the research team who “looks” like another participant). In one condition, the confederate was in a positive mood (e.g., he made a game out of throwing scratch paper in the trash bin). In the other condition, the confederate was in a negative mood (e.g., he was furious about survey items the research team was asking him).

The question then—how would the participant interpret their own psychological state?

SNEAKY AROUSAL

Lots of research suggests that arousal can amplify our emotions. For example, if you take someone who’s a little angry but then get them worked up (i.e., increase their arousal), they’ll suddenly be a lot angry. One of the tricky things about arousal, though, is that we can’t always determine when we’re aroused…

Participants were first put in either a positive or negative mindset by solving word puzzles that either brought to mind positive or negative thoughts. Then, rather than using epinephrine, researchers simply had participants do two minutes of exercise (i.e., jumping over a line) to increase their physiological arousal.

However, another group of participants was asked to wait until they felt their arousal “had returned to baseline.” As this study taught us, though, people think they’re at baseline (i.e., normal) about 2-3 minutes before they actually are.

So, when these participants rated how they felt, they didn’t think the exercise influenced their evaluations. Instead, they just reported feeling “extra” positive or negative depending on their condition.

ARE YOU AROUSED?

It can be hard to determine exactly why we feel the way we do. And as we saw with that last study, even when we think we’re normal, residual effects of arousal can bias how we’re actually feeling. So the next time you feel that faster heartrate or quicker breath, try mentally labeling that arousal to your advantage.

Or, if you want to utilize someone else’s arousal state, check out the Psychophilosophy to Ponder tod 😉

Physiologically Aroused,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: In one of social psychology’s most famous studies, researchers had a female research assistant interview male participants who were either (1) about to cross a swinging bridge, or (2) had just crossed that bridge. After speaking with the participant for a couple minutes, the research assistant asked him if she could get his phone number to go on a date. Can you guess which group was more likely to give the research assistant their phone number? Because crossing the swinging bridge generated physiological arousal (it’s scary crossing those things!), participants misattributed that arousal to the research assistant. That is, rather than thinking their feelings of arousal came from crossing the unstable bridge, they thought those feelings of arousal came from their attraction to the research assistant. In which case, the second group was more likely to give their phone number! Give you any ideas for where you should take your next first date?

Dutton, D. G., & Aron, A. P. (1974). Some evidence for heightened sexual attraction under conditions of high anxiety. Journal of personality and social psychology, 30(4), 510.

Schachter, S., & Singer, J. (1962). Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological review, 69(5), 379.

Sinclair, R. C., Hoffman, C., Mark, M. M., Martin, L. L., & Pickering, T. L. (1994). Construct accessibility and the misattribution of arousal: Schachter and Singer revisited. Psychological Science, 5(1), 15-19.

One Comment

Comments are closed.