Beginning Your Descent…

The only thing worse than a liar is a liar who is also a hypocrite. — Tennessee Williams

Right now, I am giving you the choice between taking the blue pill or the red pill.

If you like the way your story works, the perceived authenticity in your life decisions, select the blue pill and leave without reading further.

If, however, you want to see how twisted this rabbit hole gets, take the red pill, and let’s begin our descent.

…

In 1956, researchers invited participants into the laboratory to do an exceedingly boring task: remove a square peg from its hole, give it a quarter-turn, put it back in. And for an hour, participants did this. Afterward, a researcher thanked the participant for his assistance, but then asked him for a favor.

According to the researcher, his team was short staffed and they needed the participant to introduce the task to the next participant, which required telling that person just how enjoyable and fun the task was.

Of course, conveying this would be an utter lie, but the researcher promised monetary compensation: for some, the researcher offered the participant $1 to lie; for others, they offered $20. And after the participant had lied to the other person, the researchers had that original participant fill out surveys on how much he personally enjoyed the peg-turning task.

Any guesses on which group (those who received $1 vs. $20 to lie) reported liking the task more?

Answer: those who were only paid $1.

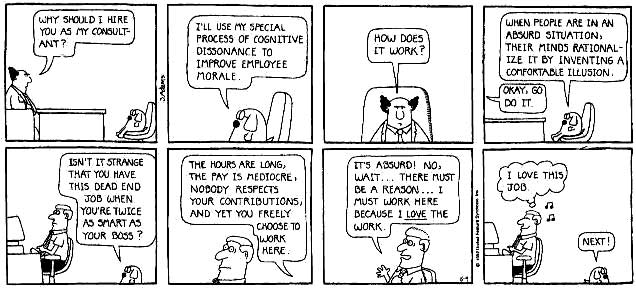

This is what we call cognitive dissonance.

The technical definition of “cognitive dissonance” is the discomfort aroused from holding two conflicting beliefs at the same time. So in the study, the participant holds the belief that “lying is bad” but at the same time knows he just lied.

Now, in the condition where the participant receives $20, he can justify his behavior: Yeah, I lied; but I got paid $20 to do it. In the other condition, though, $1 hardly seems justification for his behavior, in which case he has to come up with another explanation, namely: Maybe that task wasn’t really as boring as I remember…

And if you look around you, you’ll see this effect everywhere.

If you smoke cigarettes, there is the constant mental conflict: “I know they’re bad for me but I don’t want to do things that are bad for me.” So instead of harboring this internal disharmony, we create justifications: “maybe cigarettes aren’t that bad” or “my enjoyment outweighs their threat.”

Think also of tough decisions between alternatives, for example, which college you go to or which car you purchase. If on the one hand you have the thought, “I want the best college/car I can get,” whichever you decide on, has to be the best choice—or otherwise you live with the turmoil that you made the wrong one.

Or what about this: Do parents really love their children, or have they just convinced themselves they must love their children. For why else would they have put up with all that work to care for them if they really didn’t love them?

We’ll talk more about cognitive dissonance next week, but for now, when you freely choose to do something you dislike, try to ask yourself: why am I really doing it?

Dissonantly,

jdt