The World’s Greatest Problem

Human beings are perhaps never more frightening than when they are convinced beyond doubt that they are right. — Laurens Van der Post

People often ask me: What’s your favorite theory in social psychology? But often what I think they’re really asking is what’s the most important theory?

So let me tell you: naïve realism.

Naïve realism asserts that humans have a natural tendency to believe that the world they see is exactly the world as it exists—that they objectively perceive reality, and anyone who disagrees with them is either irrational, biased, or simply a contrarian.

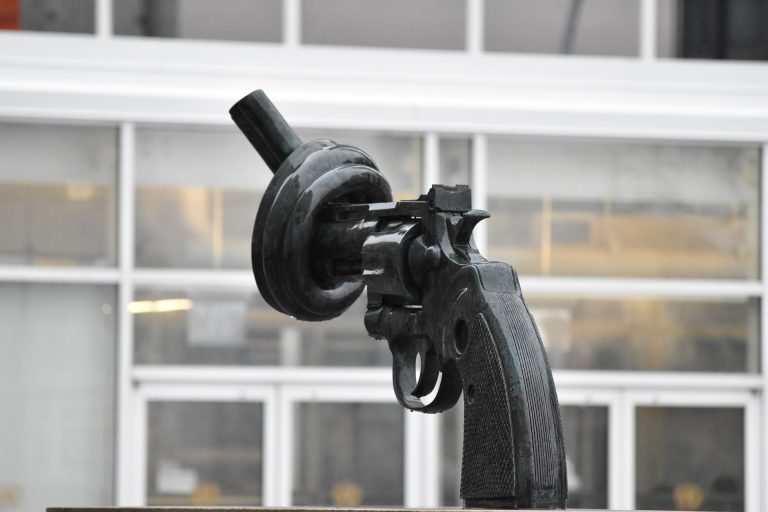

For the most basic example, take this picture to the right.

Back in 2015, this became a famous meme for its divisiveness in what color of dress you saw—black and blue or gold and white. People want to believe the world they see is the world as it really is. So when people contest something as simple yet plain as the color of that dress, it flies in the face of our naïve realism, or belief that we directly perceive the world around us.

But what actually happens when you perceive this dress?

First, light bouncing off your computer screen gets reflected in your eye, passing through your specifically sized lens and onto your specifically designed retina, before transforming into an electrical impulse in the optic nerve that gets sent along to the brain.

So tell me again how you “objectively” perceive the world?

Of course, even with all of our incomprehensibly unique brains, for the most part, we all see and hear the same things. There may be slight differences in perception, but ultimately, that dress is still not a dress people would wear. Thus, we can still get along fine even if we (mistakenly) continue to believe that we see an objective reality.

The problem, however, is that people extend this objective perceptual reality to an objective social reality, too.

That is, not only do we tend to believe that what we see is the “right way” to see, but what we think is also the “right way” to think.

And this is the crux of all the world’s problems: We believe that our interpretations and beliefs about the world are the right ones to have, and anyone who disagrees with them is either irrational, biased, or simply a contrarian (versus the other possibility that maybe we have it wrong).

But our world is incredibly ambiguous. What may be a joke to one person is indeed an insult to another. What sounds like a great idea to your friend is the dumbest idea ever to your mother. But if every time someone disagrees with us we automatically think they’re irrational or biased, instead of discussions we have arguments, instead of thinking we have shouting.

The fact of the matter is that we’ve all had different upbringings, value structures, experiences, hopes, so we are necessarily going to interpret this ambiguous world—and the best path for its success—differently. However, the only way for us to actually develop that best path is to understand that this other person came to their beliefs with a line of reasoning just like you did.

Now, this isn’t to say there are two sides to every issue. No matter how much people try to present “evidence” that the Nazi concentration camps weren’t real, I unabashedly assert that’s incorrect. Yet, just as strongly as I’m committed to my belief, others are equally opposed to it. So although one of the best ways to change someone’s mind is to first let them explain their views, you still need to “call a spade a spade.”

If someone is expressing sexist, racist, or homophobic views, you need to address that; however, don’t just condemn them, try to explain why their remarks are inappropriate.

Next week, we’ll go over specific studies that provide more empirical evidence for naïve realism, but for now, just remember: the world you see is not the same world others do.

Naively,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: One way to combat naïve realism is through a healthy dose of introspection and skepticism. For example, in the language Tuyuca, all verb-endings require that you include the manner in which you know something. That is, every time you assert something, you have to simultaneously be able to provide evidence for the claim. How would that play out if we all had to cite the reasons for our beliefs in addition to stating them?

Ward, A., Ross, L., Reed, E., Turiel, E., & Brown, T. (1997). Naive realism in everyday life: Implications for social conflict and misunderstanding. Values and knowledge, 103-135.

One Comment

Comments are closed.