Bugs in Our Brains’ Coding

Bias and impartiality is in the eye of the beholder. — Samuel Johnson

Alcohol-infused parties are rarely good places to confront someone on their socio-political beliefs. But in this real-life example, I had no choice.

The young man in the kitchen—spouting beliefs that I wholeheartedly disagreed with—woke this sleeping, glasses-wearing dragon when he exclaimed: “And there are studies to prove it.”

The young man in the kitchen—spouting beliefs that I wholeheartedly disagreed with—woke this sleeping, glasses-wearing dragon when he exclaimed: “And there are studies to prove it.”

Excuse me, sir, but I am the study-reader here.

So, raising from the couch, he, I, and some other poor schmuck that got caught in the crossfire had a debate for the next 30 minutes or so. However, no one seemed convinced by the other, because at the end of it, we all agreed on only one thing:

The other person was biased.

EGOCENTRIC BIASES

Recent research by Troy Campbell, a prominent marketing professor at the University of Oregon, sheds light on one of the most prominent biases in human cognition: the egocentric bias.

This bias describes people’s tendency to use their own thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in predicting other’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. For example, take work that Dr. Campbell has done on one type of egocentric bias known as the desensitization bias.

In one study, researchers covertly and repeatedly showed participants one of two shocking pictures (i.e., of Lady Gaga either in a black mask or crime tape). Then afterward, participants were asked: “For first-time viewers, which image do you think would be more shocking/weird?”

In one study, researchers covertly and repeatedly showed participants one of two shocking pictures (i.e., of Lady Gaga either in a black mask or crime tape). Then afterward, participants were asked: “For first-time viewers, which image do you think would be more shocking/weird?”

Overwhelmingly, people chose the picture that they hadn’t seen as much. In other words, repeated exposure desensitized (i.e., reduced) the image’s effect on the individual. However, because we think others will think and feel like we do, these participants mistakenly applied their own desensitized feelings to other people, too.

Thus, if you’ve ever had someone tell you something’s “not that bad” or “only okay,” it may be that this person has experienced that stimulus multiple times, and so they’ve become somewhat desensitized to it. In turn, they mistakenly think you’ll feel like they do, too.

NON-EGOCENTRIC CONSEQUENCES

Now, if you think these egocentric biases only lead to inaccurate food or movie recommendations (which they can), you’re wrong. These biases—in other work conducted by Dr. Campbell—can have real-world influence on the policies we support.

In a second version of this scenario, rather than purchasing a food you like, imagine the person is using their welfare to purchase something you dislike (e.g., Ho Hos—those things have way too much frosting!).

Even though in both cases the person is buying junk food, do you judge the person any differently depending on whether they’re buying food you like versus dislike?

In fact, research shows you do.

In particular, when the welfare recipient is purchasing a food we dislike (vs. like) we rate them as significantly more irresponsible with their purchase.

Because we think our own tastes and preferences are so correct, we devalue others when they choose things—even on subjective topics!—that disagree with us. And in fact, after reading a scenario where the welfare recipient purchased a disliked (vs. liked) foods, participants reported less support for funding relevant welfare programs.

THE BIAS BLIND SPOT

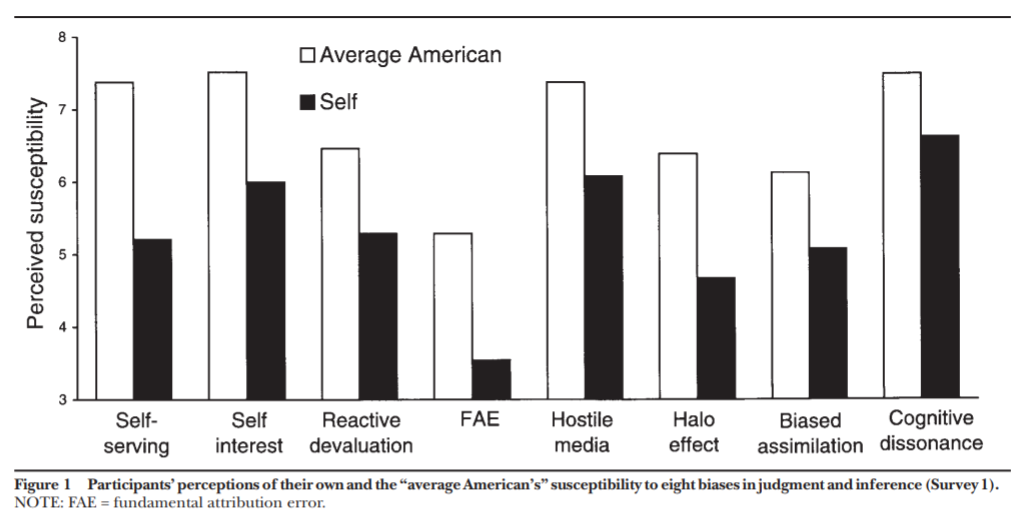

In now classic research, a series of surveys revealed that people, on average, believe others are much more prone to psychological biases (e.g., the halo effect, self-serving biases, etc.), than they are.

In fact, this is such a prominent phenomenon that it has been dubbed the bias blind spot and is regarded as individuals’ tendency to “see the existence and operation of cognitive and motivational biases much more in others than in themselves” (Pronin, Lin, & Ross, 2002; p. 369).

So, when it came to my own assessment of who was biased in the debate I described at the beginning of today’s post, who was right? Unfortunately, my awareness of my own bias toward being biased prevents me from giving you an objective answer.

(But people would agree it was me who was right.)

Maybe (but not coping to it) Biasedly,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: So with all this new knowledge, what can you do to help yourself be less biased? Well, the first step, of course, is acknowledging that there’s an issue, namely, that you’re just as prone to cognitive biases as the next person! Once you admit to that, it then becomes a matter of taking steps to combat your brain’s inherent biases. In regard to the egocentric bias we discussed today, in judging others’ attitudes and behaviors, it’s important to get input from a number of different people. Because we tend to anchor on our own opinions, making sure you have a diversity of opinions to form an “average” can help you escape your own head. But in trying to form a more accurate perception of others’ attitudes and beliefs, can you see any issues with only seeking the opinions of your friends and family?

Kim, J. Y., Campbell, T. H., Shepherd, S., & Kay, A. C. (2019). Understanding contemporary forms of exploitation: Attributions of passion serve to legitimize the poor treatment of workers. Journal of personality and social psychology.

Pronin, E., Lin, D. Y., & Ross, L. (2002). The bias blind spot: Perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(3), 369-381.

Shepherd, S., & Campbell, T. (2019). The Effect of Egocentric Taste Judgments on Stereotyping of Welfare Recipients and Attitudes Toward Welfare Policy. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 0743915618820925.

Hi J,

In this post you write: “Excuse me, sir, but I am the study-reader here.” Taken out of its context, this statement sounds biased to me. Or is it one from someone craving for recognition?

Hi Anne, thanks for the comment 🙂 I will be the first to admit I’m a biased individual, but in this instance, the other guy who was claiming he had “read studies” about the topic was simply lying (i.e., there are no studies “proving” what he claimed). Moreover, because I identify with being a researcher, being a “study-reader” feels much closer to what I do for a profession versus what he did. All of that said, does it mean I’m any less biased with my comment? As always, I’d have to have an outside party play judge for that 😉