Black Criminality

I’m for truth, no matter who tells it. I’m for justice, no matter who it’s for or against. — Malcolm X

Although the United States has progressed substantially in its treatment of Black Americans, empirical data show that Blacks have yet to receive the equality they have been promised for over 150 years.

For example, a report by the US Department of Health and Human Services shows that compared to Whites, Blacks experience between 30-40% worse access to and treatment for health care. In another study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, people with stereotypically “Black names” are 50% less likely to get a callback for a job compared to an equally skilled applicant with a White name.

When it comes to the criminal justice system, a report by the University of Michigan Law School shows that Black people—committing the exact same crime as White people—are twice as likely to be convicted and then later receive a significantly greater sentence.

That is, across health care, employment, and the law, Blacks are factually treated worse than White people.

But how could these disparities still exist? To answer that, we must look to the history of the US. For just as you couldn’t understand your personality today without understanding your childhood, so, too, must we look to the past treatment of Blacks to understand the treatment of them today.

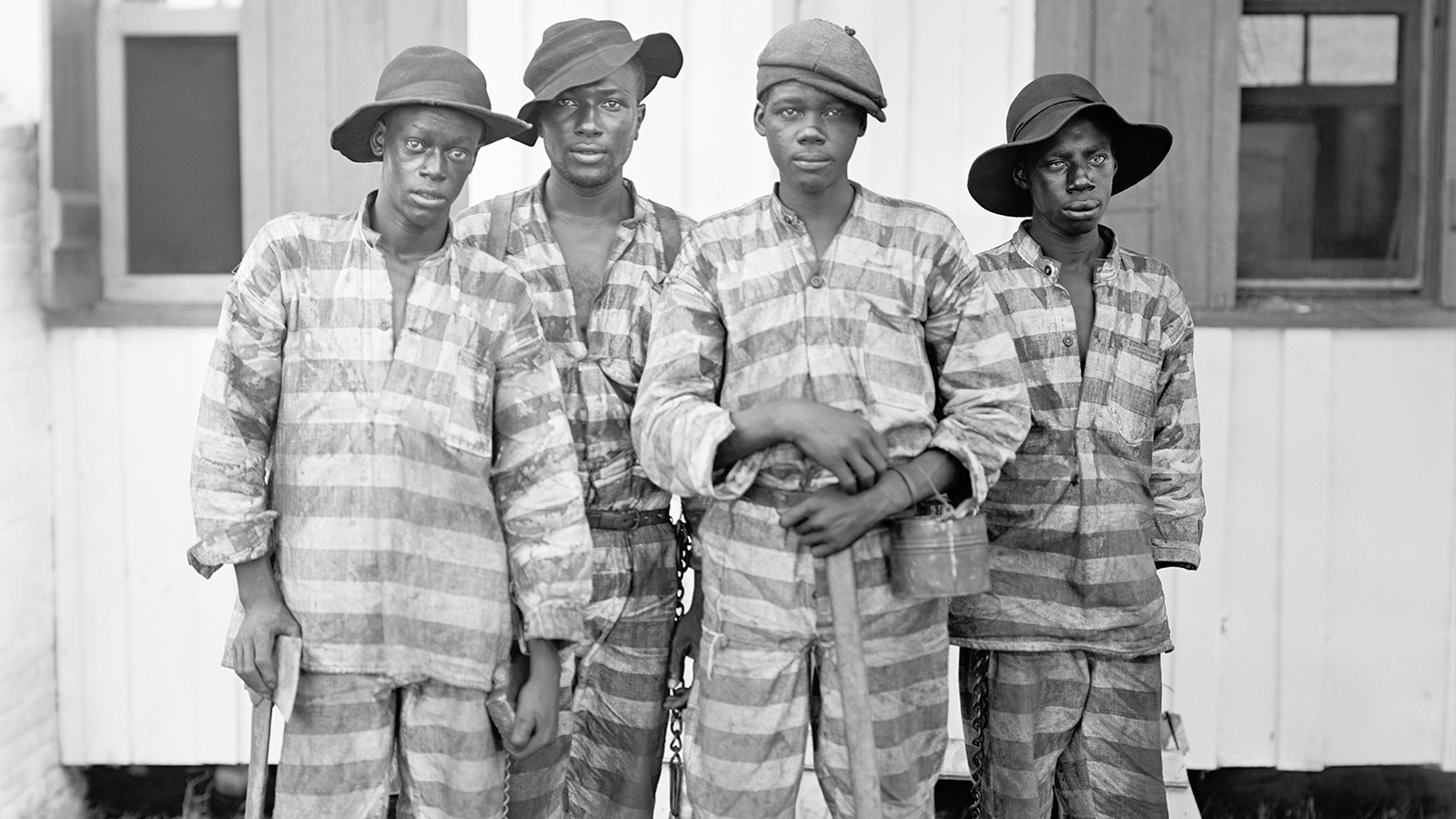

Although slavery was supposed to end in 1865 with the Thirteenth Amendment, right afterward, Southern States quickly instituted laws known as the “Black Codes.”

The Black Codes were a set of laws specifically intended to arrest Black people. For example, if Blacks didn’t sign a yearly labor contract (for underpaid wages), they could be arrested. If Blacks simply looked unemployed, they could be arrested. If Blacks were caught loitering or living in a “disorderly house,” they could be and were arrested.

It didn’t matter the charge, really, so long as the Southern States could fill jailhouses with Black people, for there was an important loophole in the 13th Amendment:

By arresting Blacks, then, these agricultural societies could maintain their free labor while still “abiding by the laws of the land.” However, as a result of this Black imprisonment, this powerful “criminal stereotype” was readily applied to Black people.

Aggressive, dishonest, untrustworthy—these were the criminal associations the White majority quickly labeled Black people, an image that was further validated by the media.

For example, in 1915, the silent film, The Birth of a Nation—at the time, regarded as one of the greatest filmmaking masterpieces ever —flatly portrayed Black people as unintelligent, violent, and deserving of extermination by the “heroic” Klu Klux Klan.

So, if a White person at that time (or any time really) had never interacted with Black people—as was common with that period’s racial segregation—what kind of impressions do you think they would form about Black people? And how would those influence what they taught their children?

Fast-forwarding to today (which isn’t a whole lot of fast-forwarding), Blacks are not portrayed much more favorably. For example, if you look at how White and Black criminals are portrayed on the news, Blacks are significantly more likely to be portrayed nameless, with menacing photos, and under physical restraint by police officers.

This all, of course, has very damaging effects.

Research shows that this overrepresentation of Blacks in crime-related news (and on television and in movies!) strengthens the cognitive associations of “Black” and “criminal,” such that these stereotypes come to mind much more quickly and influentially than they do for other races.

So, if we return to the health, employment, and law disparities we began with, much of them can be attributed to the automatic “criminal stereotypes” held against Black people. In cases where health practitioners can decide who gets treated next, when employers have to choose between multiple qualified applicants, when a jury has to determine”how guilty is he?,” these stereotypes exert their influence. For although we would like to believe we live in a “post-racial” society, treatment is still very much dependent on the color of our skin. And in a society that is still very much segregated, we only have the news and media to inform our perceptions which shape our interactions with other races.

Matter-of-factly,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: You may wholeheartedly agree that Black people are equal to White people, but if you were walking down the street at night, would you be more frightened by a Black or White person approaching you? If you were sitting in your car, would you be more likely to lock the door if a Black or White person was walking by? Both reactions are a result of prejudice and the first step to overcoming that prejudice is acknowledging it exists.

Dixon, T. L., & Linz, D. (2000a). Overrepresentation and underrepresentation of African Americans and Latinos as lawbreakers on television news. Journal of communication, 50(2), 131-154.

Dixon, T. L., & Linz, D. (2000b). Race and the misrepresentation of victimization on local television news. Communication Research, 27(5), 547-573.

Mastro, D., Lapinski, M. K., Kopacz, M. A., & Behm-Morawitz, E. (2009). The influence of exposure to depictions of race and crime in TV news on viewer’s social judgments. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 53(4), 615-635.

Great post JDT. The legal system in our country has systematically betrayed black americans for generations. One thing I’ve thought of, and would like your feedback on, is that defendants should have the option to NOT appear in front of a jury. They should have the option to be referred to simply as ‘Defendant’ in court documents and have no identifying information about them shown. It will be just witnesses, evidence, etc., but they have the option to remove themselves, their name, racial identity, and gender, etc., from the court.

You’ve proven (and many others have too) that Justice is not blind, so if justice isn’t blind, we can at least make the jurors blind.

REALLY great thought, Dan. Unless race is somehow related to the crime (e.g., a hate crime), we should try to remove any information about the defendant related to race, sexuality, even physical attractiveness. As you likely know, attractive people are less likely to be convicted of the crime, but if they are, they tend to receive a significantly shorter sentence compared to less attractive people.

All in all, our criminal justice system could use an overhaul. Especially when *97% of all imprisoned criminals* never even went to trial (i.e., they took plea bargains).

I lock my car doors to either a white or black person apprnoaching.

Ha That’s good to be non-discriminatory in your cautiousness