What is the Placebo Effect?

Life is so constructed, that the event does not, cannot, will not, match the expectation. — Charlotte Bronte

My dad has tried some unusual remedies to resolve his ailments (e.g., magnetic bracelets supposed to realign your chi but actually destroy your laptop’s hard drive); however, one of his voodoo concoctions I was actually persuaded to try were zinc supplements.

Initially, I had ridiculed his Dr. Quack advice, but when I got sick, I figured: It couldn’t hurt, right? And three years later, those tiny pills I get from CVS have prevented any illness greater than a mild sore throat.

Or is it all just placebo?

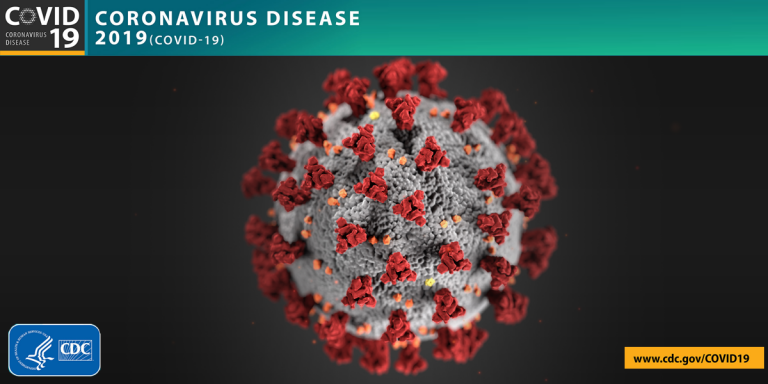

For example, studies have looked at patients taking pain pills or a placebo (i.e., sugar pills) and about 35% of those taking the fake medicine report reduced discomfort to the same extent as those taking the real medicine.

Broadly speaking, placebos work through expectations. For example, researchers gave post-surgery patients a small dose of diazepam (a medically tested anxiety reducer). However, for half of the patients, this medication was given openly (i.e., a doctor visibly gave it to them and explained its intended effects), while the other half were given it secretly (i.e., the drug was administered covertly through their IV).

Now, for those who knew they were receiving the medicine, their anxiety reduced by about 25%. But for those given the exact same medicine in secret showed absolutely no change.

This study and others show two important findings: 1) even for real medications, expecting its effects greatly increases its effectiveness, and 2) in order for placebos to work, you must expect that it will have some effect.

So what happens if you know a placebo is a placebo?

In another study, researchers brought in 80 patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome and gave them some general information about the placebo effect: (a) the placebo effect is powerful, (b) the body can automatically respond to taking placebo pills, (c) a positive attitude can help but isn’t necessary, and (d) actually taking the placebo is critical.

After this explanation, half of the participants received a bottle of clearly labeled placebo pills (i.e., a doctor told them they were inert sugar pills), while the other participants were given nothing. Incredibly, those who took the sugar pills reported significantly reduced symptom severity, increased relief, and a greater quality of life!

Now, researchers really aren’t sure why the placebo effect happens, but the leading explanation is called response expectancy theory.

For example, imagine it’s a hot summer day and you see the ice cream truck in the distance. Automatically—without even having a lick of dessert—you already feel better. Why? Well, over time, you have built up the expectation that when you see the ice cream truck, you’ll get to eat some ice cream, and when you eat that ice cream, you’ll feel better.

In essence, your brain is confident enough that this expectation will come true that your body starts acting like it’s already happened.

In fact, some researchers contend that if you look at the history of prescientific medicine, it is really a history of the placebo effect. And when it comes to my dad, the same thing may be true. But if taking zinc has kept me from sickness for multiple years, I don’t care how it works.

Stuffy noses are the worst.

Placeboly,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: Research shows that people respond much more positively to name-brand pain pills compared to generic ones–even when people are informed of this bias! Turning to your own life, what are some areas where your expectations for a particular outcome influence your actual experience of it?

Benedetti, F., Maggi, G., Lopiano, L., Lanotte, M., Rainero, I., Vighetti, S., & Pollo, A. (2003). Open versus hidden medical treatments: The patient’s knowledge about a therapy affects the therapy outcome. Prevention & Treatment, 6(1), 1a.

Kaptchuk, T. J., Friedlander, E., Kelley, J. M., Sanchez, M. N., Kokkotou, E., Singer, J. P., … & Lembo, A. J. (2010). Placebos without deception: a randomized controlled trial in irritable bowel syndrome. PloS one, 5(12), e15591.

Schwarz, K. A., Pfister, R., & Büchel, C. (2016). Rethinking explicit expectations: Connecting placebos, social cognition, and contextual perception. Trends in cognitive sciences, 20(6), 469-480.

The neurochemistry underlying placebo and nocebo effects is just fascinating. For instance, Benedetti and his group have shown that verbal warnings of future pain induce anxiety and trigger the release of cholecystokinin(CCK). CCK in turn actually makes people more sensitive to pain.

This is why you should never warn someone with a 3-2-1 countdown before you stick them with a needle or swab alcohol on a wound. The longer the warning, the more time for CCK release.

Or, I suppose, do warn them if you don’t like them very much.

To me, the neurochemistry is the much more fascinating aspect of this research! (though, I wasn’t sure how interested others would be in it, so I tried to shy away from it ha) I had no idea about the verbal warnings of future pain, though! That’s some freaking cool research. In my own studies for this post, I found a number of papers on pain and placebos showing activation in the “reward centers,” which some suggested is a sign that we perceive medicine as a “reward” in some sense, and this accounts for some of the biological improvements.

A study that’s really fascinating to me is where they gave asthmatics either a real inhaler or a fake one, and although both resulted in the participants saying that their ailment was alleviated, only those who used the real inhaler actually showed markers of reduced inflammation (or whatever the marker for reduced asthma is). In which case, we really have an example of “mind over matter” where the subjective perception obscures the lack of biological improvement!