Becoming Luckier

You never know what worse luck your bad luck has saved you from. — No Country for Old Men, Cormac McCarthy

Are you or is someone you know a lucky person? Have you ever wondered how they became so lucky? Or, like many people, do you think luck is just a fictional concept?

Today, we’ll explore the concept of luck to understand how you can use it to improve your own life.

BEING LUCKY VS. FEELING LUCKY

First, it’s important to distinguish between chance and luck.

In both cases, they refer to imperceptible and “random” events influencing a particular outcome. For example, imagine you won tickets to a concert by being the 7th caller to a radio show. On the one hand, you may think it was random chance that you won, or, you may think it was good luck.

Thus, if you believe in luck, you believe that people can exert some kind of control over outcomes that would otherwise be considered random.

Now, regardless of whether or not luck actually exists, what really matters is people’s perception of its existence. And from one line of research, believing in luck can actually be good for you.

Researchers Maia Young and her colleagues measured participants’ belief in luck alongside participants’ achievement motivations (i.e., how willing people are to persist at and pursue their goals). And across two different samples of participants, the more people believed in a stable characteristic of luck, the higher their achievement motivation.

In other words, the luckier people felt they were, the more capable and motivated they felt in pursuing their more ambitious goals!

BECOMING LUCKIER

Now, even if you perceive that luck exists, that doesn’t mean you necessarily believe yourself to be lucky. So, what can you do to personally feel luckier?

Afterward, the researchers measured how much participants would be willing to gamble on a lottery ticket. Presumably, the more they were willing to pay, the luckier they felt about their assigned numbers.

As it turned out, participants who had their numbers calculated for them (vs. randomly assigned) gambled more on the lottery. That is, these participants enjoyed the process of receiving their numbers, which in turn made them feel luckier. In other words, the more we enjoy an activity, the luckier we feel at it!

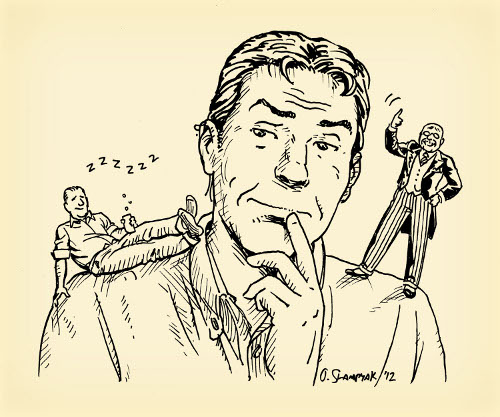

However, probably the surest way to increase your feeling of luckiness deals with the counterfactuals you mentally generate.

That is, if something bad happens to a person, but they think about how it could have been worse (i.e., they generate a downward counterfactual), people report feeling lucky. In contrast, if something bad happens to a person but they think how it could have been better (i.e., they generate an upward counterfactual), people tend to report feeling unlucky.

In other words, the more you generate downward counterfactuals (i.e., the more you focus on how things could have gone worse), the luckier you will tend to report feeling.

However, for some of the participants, right before they received the modest win, it either looked like (1) they were going to lose a lot of money, or (2) they were going to win a lot of money.

Immediately after this, the researchers had participants bet on another game of luck, roulette. And here, participants who had nearly lost money (i.e., those who made a downward counterfactual) proceeded to gamble significantly more money than those who had nearly won a lot of money (i.e., those who made an upward counterfactual).

In other words, focusing on how things could have gone worse made the participants feel luckier overall!

GOOD LUCK CAN MEAN BAD OUTCOMES

Moreover, feeling lucky can lead you to behave more negatively toward others. For example, research shows a positive relationship between how lucky you feel and how willing you are to commit antisocial acts. That is, people who perceive themselves as luckier believe they will have a greater chance at avoiding punishment for their misdeeds.

So, after reading all that, do you think yourself lucky? Or better yet, do you want to be?

Luckily,

jdt

Everyday Psychology: In today’s post, we talked a lot about whether you yourself feel lucky or not. But what about your perceptions of other people’s luck? In one interesting study, researchers found that Republican/conservative participants (vs. Democrat/liberal participants) were less likely to believe in temporary experiences of good or bad luck. Consequently, when bad outcomes happened to other people, conservatives were more likely to blame the person themselves for the bad outcome. In contrast, liberals were more likely ascribe the bad outcome to external forces. With this in mind, how might perceptions of luck influence policy decisions? How might support for different social initiatives or programs differ as a function of whether you good or bad luck influences people’s lives?

Goodman, J. K., & Irwin, J. R. (2006). Special random numbers: Beyond the illusion of control. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99(2), 161-174.

Wohl, M. J., & Enzle, M. E. (2002). The deployment of personal luck: Sympathetic magic and illusory control in games of pure chance. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 28(10), 1388-1397.

Wohl, M. J., & Enzle, M. E. (2003). The effects of near wins and near losses on self-perceived personal luck and subsequent gambling behavior. Journal of experimental social psychology, 39(2), 184-191.

Young, M. J., Chen, N., & Morris, M. W. (2009). Belief in stable and fleeting luck and achievement motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(2), 150-154.

Zhao, H., Zhang, H., & Xu, Y. (2016). Does the Dark Triad of personality predict corrupt intention? The mediating role of belief in good luck. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 608.